Italy Punches Below Its Weight on the European Defence Fund

Italy is one of the pillars of the European defence technological and industrial base (EDTIB). The peninsula is home to some of the world’s most important defence companies, with the state-controlled prime contractor Leonardo Spa, the trans-European MBDA and shipmaker Fincantieri ranking in the top fifty defence companies by sales.[1] These industries have a global reach and excel in crucial sectors such as rotary wings vehicles, electronics and more.

However, it is becoming more and more clear that, on the European stage, Italian companies struggle to convert industrial and technical capabilities into project leadership. One just needs to observe the modest role that Italian aerospace and defence companies play in a key European cooperative programme, the European Defence Fund (EDF). Despite Rome’s involvement in previous initiatives enhancing European cooperation on defence research and development (R&D),[2] the two first EDF rounds have seen Italy unable to exercise a degree of industrial and technological leadership corresponding to its industrial weight. While the sample is still too little to extrapolate a trend, a comparison to the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) suggests that policy action is badly needed to bolster Italy’s role in EDF.

The European Defence Fund (EDF)

The EDF was created by the European Commission in 2019 to fund joint R&D projects in the realms of aerospace and defence. From an industrial and technological perspective, the idea is that the promotion of pan-European technological innovation would strengthen Europe’s strategic autonomy, as well as enhance greater cooperation and consolidation of the EDTIB. From a military and procurement perspective, the hope is that one day the technologies financed through EDF will form the bedrock of European weapon systems and equipment common to several member states and capable of competing on foreign markets with products from third-country rivals.[3]

For countries like Italy, the EDF is particularly important: technological sophistication is central to the way Western countries, especially medium-sized powers that cannot rely on combat mass, can gain a battlefield advantage over potential adversaries. Moreover, joining forces at the European level is paramount to achieving the economies of scale that would allow the EU to play in the same league as the United States, China or Russia.

The Fund is managed by the Directorate-General for Defence Industry and Space (DG DEFIS) and allocates 8 billion euro from the EU budget over the 2021–27 period.[4] EDF is based on yearly competitive tenders in which multinational consortia of companies and research institutions from the EU and Norway compete in calls for proposals; the winning consortia are awarded funds that mostly cover the costs of the selected project. Clearly, 8 billion euro over seven years are insufficient compared to R&D funds allocated by the likes of China or the US – the Pentagon, for instance, has requested a budget of 145 billion dollars for 2024.[5] Nevertheless, the initiative is a very important first step towards the consolidation of the EDTIB.[6]

Italy in the 2021 and 2022 EDF tenders: A modest role

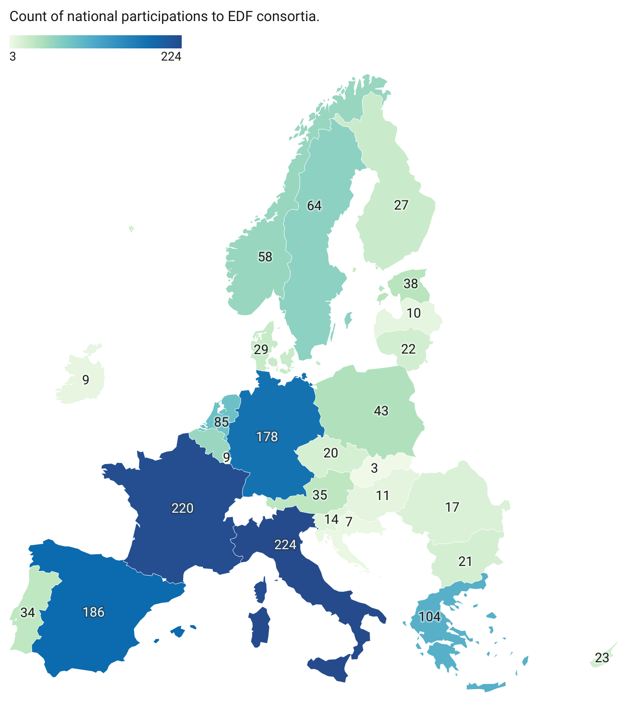

The first EDF call for proposals was published in 2021, while the results of the 2022 round were released in mid-2023. The position of Italy in these first two rounds is twofold. On the one hand, Italy is the member state with the highest degree of participation in selected projects, with 224 instances[7] of Italian entities participating in the 101 projects financed to date, just ahead of France’s 220 participations (Figure 1).[8] Italy is the third country in terms of EU funds received, at least when analysing the available data: according to existing research,[9] Italian entities were awarded 135 million euro under EDF 2021 (15 per cent of the overall funds allocated that year), just below Germany’s 138 million and France’s 236 million euro.

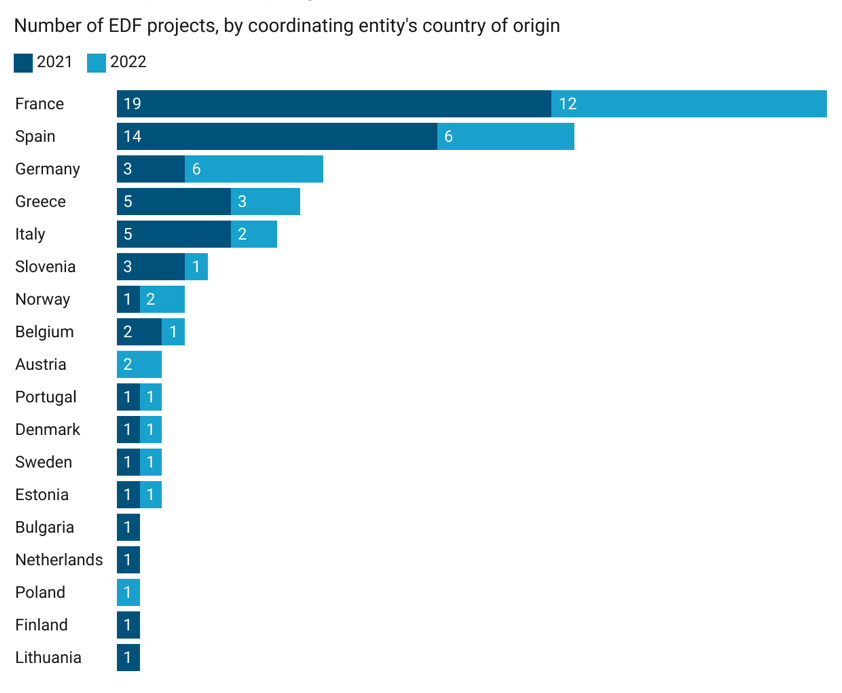

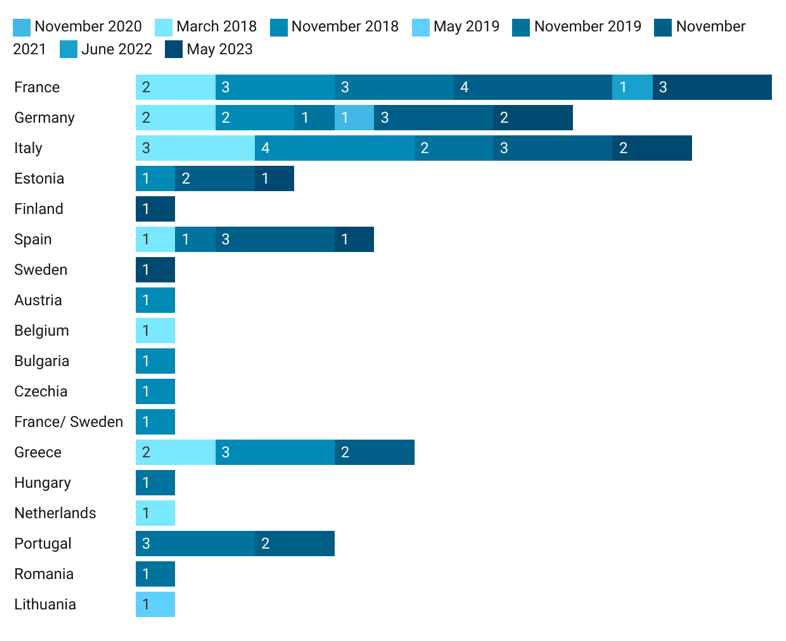

However, Rome is only fifth in terms of coordination, leading just seven projects: this is slightly less than Greece, a third of those led by Spain, and a quarter of France’s. In particular, Italy’s effort to lead slowed down in 2022, as Italian companies took over the coordination of just two projects compared to France’s twelve and Germany’s six (Figure 2). It should also be noted that German companies tripled the number of coordinated projects compared to 2021, showcasing a renewed interest by German industry in European cooperation.

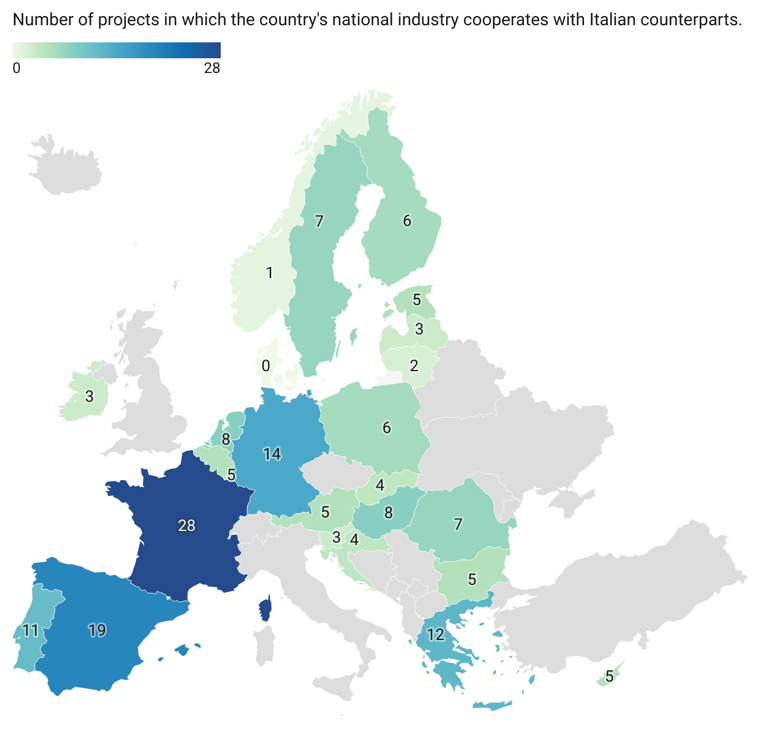

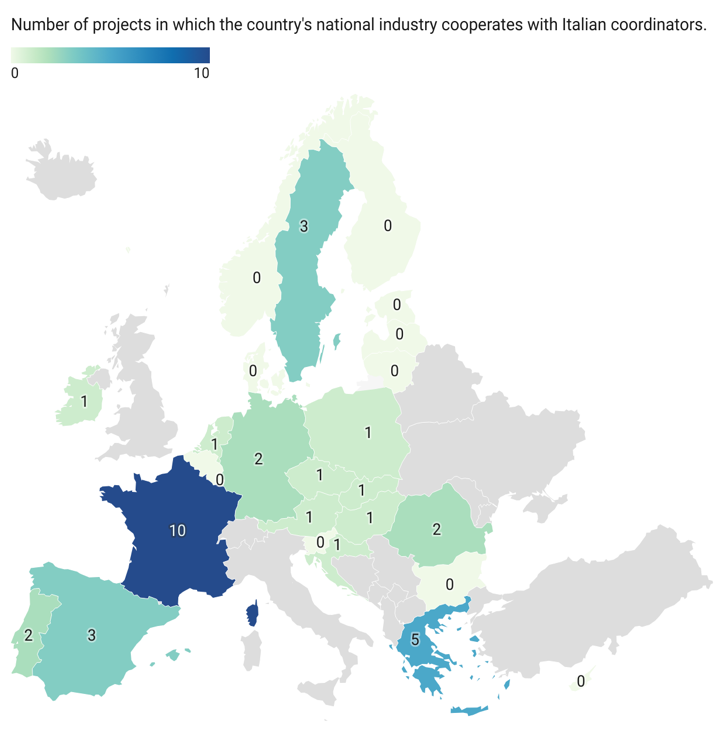

With regard to the geographic configuration of the EDF consortia in which Italian companies are part, Italian entities mostly cooperate with counterparts from France (on 53 projects), Spain (53 projects), Germany (49 projects) and Greece (35 projects). In the first two rounds of EDF, however, Italian entities seldom exercise leadership roles over French entities, something that instead happens in PESCO projects.

Coordinating EDF consortia matters. Guiding companies bear the cost of aggregating heterogenous, complex actors, but also benefit from gaining an overview of the technologies held by the individual partners. Moreover, project coordinators exercise a crucial agenda-setting power and can decisively influence the direction taken by the project, also with the perspective of leading a possible production phase. Finally, coordinators also assert political and organisational leadership that, through will, inertia or habit, becomes entrenched and reflected in future EDF consortia.

Figure 1 | Instances of participation to EDF projects

Figure 2 | Leadership of EDF projects

Source: own elaboration based on EDF factsheets.

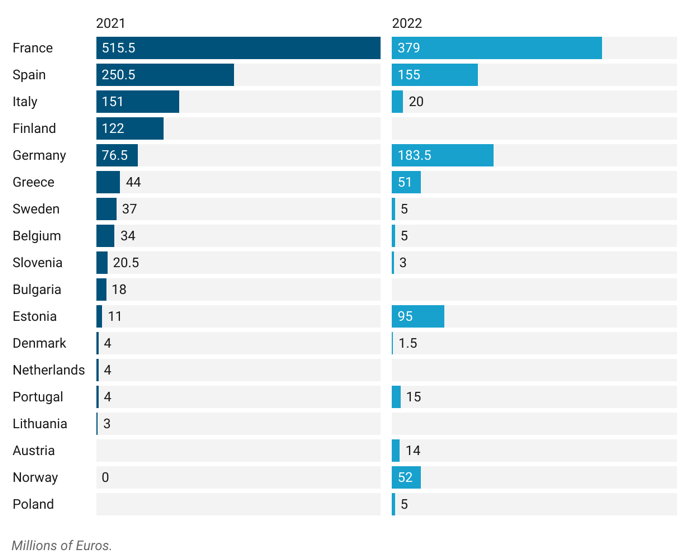

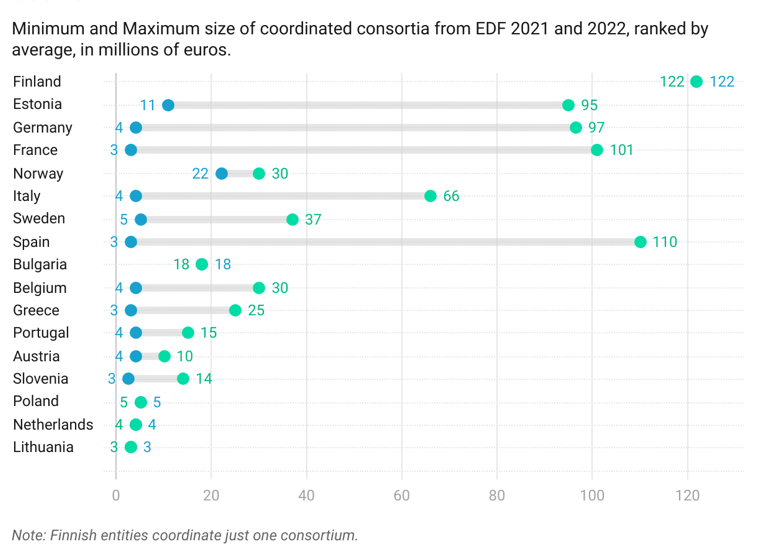

The role of coordinator is especially delicate in large, big-ticket consortia. The value of consortia does not just matter in terms of net monetary gain for the industry. If we use the value of projects as a rough, imperfect indicator of a project’s technological complexity and sophistication, then it becomes clear which countries have gained a leading edge through their national industries. Here too, Italian entities play a secondary role compared to other actors populating the EDTIB. French entities coordinate projects worth a total of 894.5 million euro, a figure dictated by Paris’ excellent performance in both the 2021 and 2022 rounds. Italy, on the other hand, saw an 85 per cent drop compared to 2021 in the value of coordinated projects, from 151 million euro to just 20 million (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3 | Value of coordinated EDF projects by coordinator’s country of origin

Figure 4 | Value of coordinated EDF consortia by coordinator’s country of origin

Source: own elaboration based on EDF factsheets.

Comparing Italy’s EDF performance to PESCO engagement

Overall, Italy has not been able to establish itself as a leader within the framework of EDF. Yet, there is no reason why Rome should not be capable of playing a more prominent role. Indeed, Italy has proven to be far more proactive in another important European R&D format, the PESCO. The first PESCO projects were launched in 2018, growing through successive waves to 74 in July 2023.

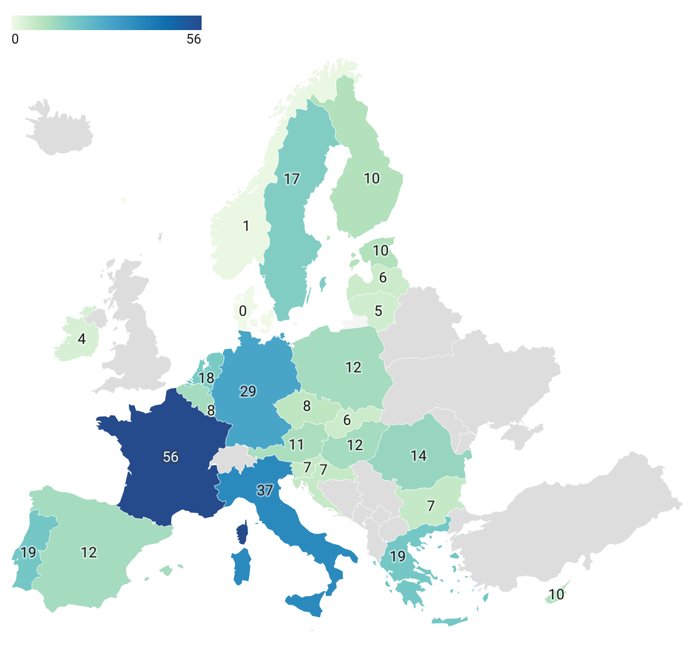

Here, Italy holds a leadership role commensurate to its economic weight. Rome is second only to Paris in terms of coordinated projects (Italy leads 14 projects, France 16), a figure that also reflects their respective participations in PESCO projects (37 for Italy, 56 for France) (Figures 5 and 6). Italy’s effort to bring home new PESCO projects to coordinate also seems to be consistent throughout different project waves. Moreover, the geographic distribution of Italian leadership more closely resembles that of Italy’s partnerships: for instance, Italy is indicated as coordinator in 35 per cent of the projects it pursues with France and 40 per cent of those it pursues with Greece (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 5 | Number of participated PESCO projects

Figure 6 | Coordination of PESCO projects

Figure 7 | Italian partners in PESCO projects

Figure 8 | Countries led by Italy in PESCO projects

Source: own elaboration based on PESCO data.

Notably, unlike the EDF, PESCO is an intergovernmental arrangement which fosters defence cooperation without funding from the EU budget. In EDF projects, national authorities can only play a supporting role to the efforts of the respective national industries, which participate in competitive tenders; in PESCO, governments are in the driver’s seat, as the respective Ministries of Defence (MoD) are the ones that establish cooperative projects. The limited involvement of MoDs in the EDF compared to PESCO is a consequence of different approaches to defence integration. EDF, it has been argued, is a supranational scheme that challenges the intergovernmental paradigm of existing European defence policies.[10] By choice and design, the main actors are not governments, but individual industrial actors.

While it is too early to issue a final judgement on Italy’s performance in EU defence cooperative formats, it may be reasonable to infer that the institutional set-up of the two formats (PESCO being a purely intergovernmental forum, while EDF a more community-based and transnational arrangement) may determine varying levels of engagement. This may be (also) due to the far-from-frictionless coordination between defence companies and Italian government authorities, which are institutionally less proactive than their foreign counterparts in getting involved in EDF.

What lacks in Italy’s approach to EDF, and how to improve it

A lack of willingness or ability by Italian companies to lead consortia on EDF tenders could cost the Italian industry dearly. In 2022, the calls for proposals were focused on topics on which Italy has a comparative advantage within the EDTIB, especially in terms of enabling or strategic capabilities: missile defence, sensor technology, but also cutting-edge technologies such as remotely piloted or autonomous vehicles. The 2023 calls for proposals also present many opportunities for Italy. In fact, the projects selected by the Commission will again cover topics such as unmanned systems, but also issues pushed into the spotlight by the war against Ukraine: armoured vehicles, artillery, strategic air transport, space reconnaissance and underwater surveillance.[11]

So, what could Italian government authorities do to improve the country’s performance in EDF calls? To be sure, as mentioned, EDF has been designed as a supranational tool in which governments play a lesser role compared to other defence initiatives, like the intergovernmental PESCO. However, the sensitive nature of defence cooperation means that national authorities still have to perform some roles that cannot be carried out by businesses, both in terms of overall strategic steering, facilitating cooperation and regulating cross-border transfers of technology. Data also shows that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) make up a proportionally higher percentage of Italian instances of participation (28 per cent) compared to France (20 per cent) and Germany (18 per cent).[12] This is noteworthy because, as recognised by the European Defence Agency (EDA), SMEs require special support by their MoDs compared to prime contractors.[13]

Frictionless cooperation between companies and the respective MoDs is thus crucial. The intergovernmental format of PESCO forced such cooperation from the get-go. Anecdotally, during the first rounds of EDF, some MoDs were still in the process of internally structuring their own contribution and understating the dynamics of the novel instrument. Yet, at any rate, under the supranational veneer, member states can exercise significant influence over EDF processes, both de iure and de facto.[14]

From this perspective, the Italian MoD should strive towards a more proactive role, as it did with good results during the EDF predecessors – the Preparatory Action on Defence Research and the European Defence Industrial Development Programme – up to the first 2021 calls. Such a role entails two main lines of action: first, a stronger and more timely internal coordination among the branches chiefs involved in actively supporting and shaping the business decisions of staff, their national armament directorate, the single services and the minister’s cabinet; second, a greater pressure on national industries to raise their level of ambition, take the risk and coordinate consortia, also by providing a national framework through which Italian companies can coordinate to pursue such topics.

At the European level, the MoD should take an interest in encouraging pertinent authorities to define EDF calls that are both relevant to Italy’s strategic interests and formulated in such a way to fully capitalise on the strengths of the Italian industry. Moreover, the MoD should encourage matchmaking between prime contractors and SMEs during the formation of consortia, and provide support once projects are awarded (for example, in terms of security clearances and export control procedures), as well as create a national platform through which Italian companies can coordinate in order to speak with one voice to foreign partners. These steps are also key to putting Italian companies in the position to step up as coordinators and enable, when necessary, the launch of follow-up projects in successive EDF rounds.

The bottom line is that, given the crucial role played by Italian defence companies, Rome’s active participation in EDF is paramount for its success. National institutions and companies need to step up and ensure that Italy’s net contribution is proportional to its technological and economic power.

Michelangelo Freyrie is Junior Researcher in the Defence and Security Programmes at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

[1] Lucie Béraud-Sudreau et al., “The SIPRI Top 100 Arms-producing and Military Services Companies, 2021”, in SIPRI Factsheets, December 2022, https://www.sipri.org/node/6079.

[2] Ester Sabatino, “Padr e Edidp: come si muove la difesa italiana nei nuovi progetti europei” [Padr and Edidp: how Italian defence moves into new European projects], in AffarInternazionali, 30 June 2020, https://www.affarinternazionali.it/archivio-affarinternazionali/?p=82647.

[3] Alessandro Marrone, “National Expectations Regarding the European Defence Fund: The Italian Perspective”, in Ares Group Comments, No. 42 (October 2019), https://www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/ARES-42-EDF-Italy.pdf.

[4] European Commission, The European Defence Fund (Factsheet), 30 June 2021, https://europa.eu/!wpQMx9.

[5] Courtney Albon and Colin Demarest, “Pentagon’s Historic R&D Request Has Billions for Advanced Networks, AI”, in C4ISRNET, 13 March 2023, https://www.c4isrnet.com/battlefield-tech/2023/03/13/pentagons-historic-rd-request-has-billions-for-advanced-networks-ai.

[6] Gueorgui Ianakiev, “The European Defence Fund. Game Changer for European Defence Industrial Collaboration”, in Ares Group Policy Papers, No. 48 (November 2019), https://www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ARES-48.pdf.

[7] Since single entities can participate in multiple projects, instances of participation do not correspond to the overall number of involved entities.

[8] Data elaborations exclude EOA – Enhanced Opportunities for All, a “meta-project” which aims at improving matchmaking between companies within the EDF and does not result in the R&D of specific combat capabilities.

[9] Hélène Masson, “European Defence Fund. EDF 2022 Calls Results and Comparison with EDF 2021”, in FRS Presentations, 17 July 2023, https://www.frstrategie.org/sites/default/files/documents/specifique/2023/EDF2022-2021-STATS.pdf.

[10] Pierre Haroche, “Supranationalism Strikes Back: A Neofunctionalist Account of the European Defence Fund”, in Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 27, No. 6 (2020), p. 853-872, DOI 10.1080/13501763.2019.1609570.

[11] European Commission, European Defence Fund: €1.2 Billion to Boost EU Defence Capabilities and New Measures for Defence Innovation, 30 March 2023, https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/node/443_en.

[12] Hélène Masson, “European Defence Fund”, cit.

[13] European Defence Agency, Guidelines Facilitating SMEs’ Access to the Defence Market, June 2015, https://eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/documents/guidelines-for-facilitating-smes’-access-to-the-defence-market_june-2015.pdf.

[14] Ester Sabatino, “The European Defence Fund: A Step towards a Single Market for Defence?”, in Journal of European Integration, Vol. 44, No. 1 (2022), p. 133-148, DOI: 10.1080/07036337.2021.2011264.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, July 2023, 8 p. -

In:

-

Issue

23|38