Titolo completo

The Mattei Plan for Africa: From Aid to Partnership? Recommendations for the 2026 Italy-Africa Summit

|

Since its launch in January 2024, the Mattei for Africa has become the driving force of Italy’s foreign and development policy towards Africa, with an unprecedented level of political investment in the Continent that has raised high expectations among both African[1] and European partners. The Plan is framed as a long-term, non-predatory partnership aimed at fostering shared prosperity across six main pillars.[2] It represents a significant strategic pivot, centralising Italy’s Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) and economic diplomacy under a single framework. In the past two years, the Plan has followed an incremental approach, significantly expanding the number of countries and projects carried out. Based on the Government’s second annual report to the Parliament on the Mattei Plan delivered in June 2025,[3] four salient developments can be outlined.

First, the Steering Committee (Cabina di Regia), chaired by the Prime Minister, was fully operationalised, ensuring a high-level political direction. In addition to diplomatic staff, the Steering Committee team was expanded with a series of seconded experts from major industrial conglomerates (e.g. Eni, Enel, Leonardo, to name a few), which helped increase coordination with the private sector.

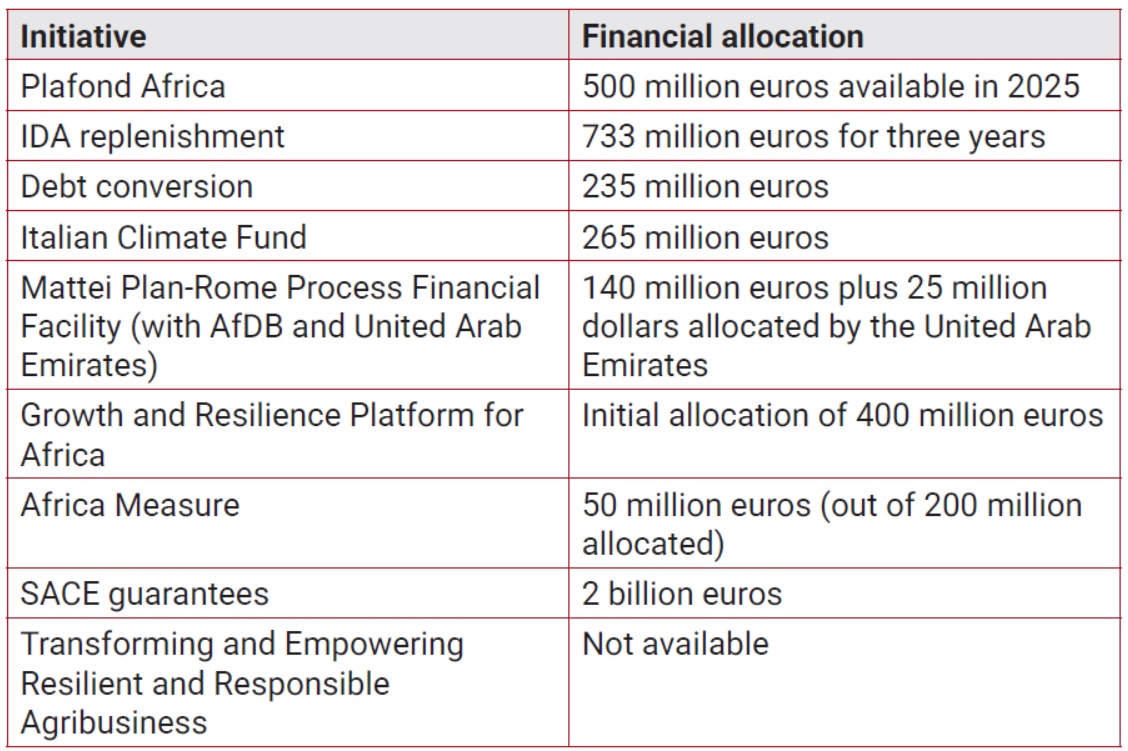

Second, several new financial initiatives were rolled out with a wider range of national and international partners involved (Table 1). At the moment, there is a dual pace of implementation, with 29 initiatives already operational and 35 in early stages.[4] The projects are distributed across the six pillars, with the largest share in education and training (24 initiatives), followed by energy (14), and water/infrastructure (12).

Table 1 | Key financial resources mobilised

Source: Mattei Plan Steering Committee, May 2025.

Third, the geographic extension of the Plan was significantly expanded, adding five new nations (Angola, Ghana, Mauritania, Senegal and Tanzania) to the initial nine partner countries, bringing the total to 14 African nations. The introduction of Angola, which is key to the development of the Lobito corridor, was particularly significant, as this country was not included in the list of priority countries published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in its Three-year Programming and Policy Planning Document for 2024-2026.[5]

Fourth, the Government has invested a lot politically in internationalising the Mattei Plan[6] by formalising a stronger alignment and synergy with the European Union’s Global Gateway at the June summit in Rome.[7] This summit marked a fundamental milestone to show the Plan’s full integration into the ‘Team Europe’ approach, as well as to announce the co-financing of key initiatives such as the Lobito Corridor infrastructure project, the development of climate-resilient value chains like coffee and the expansion of the Blue Raman submarine cable, with an overall value of the shared financial commitments amounting to 1.2 billion euros.[8]

What has worked: Strengths and opportunities

Despite initial scepticism, in less than two years, the Mattei Plan has already achieved at least four positive spill-over effects. To begin with, the Plan’s centralised governance structure, the strong political investment of the Prime Minister, as well as the inclusion of high-level political figures, ensure that the Plan is a strategic priority for the Government. This not only proves a cohesive vision that has long been requested by African partners, but also pushes all actors involved in Italy’s development cooperation policy to work as a real system. As an example, the Steering Committee has also steered the creation of ad hoc working groups that were key to unlocking financial projects in Africa, where national companies and commercial banks were reluctant to invest due to increasing levels of debt distress of recipient countries, such as the Koysha dam in Ethiopia. In addition, the Committee’s structure, which integrates seconded staff members from key financial institutions (e.g. the national development finance institution Cassa Depositi e Prestiti, as well as the export credit agency SACE), as well as major state-controlled enterprises, has brought a result- and business-oriented methodology that is essential to boost de-risking tools and pool private resources to bridge the ODA gap. This is particularly crucial in a context where polycrisis is putting national budgets under stress, making it very unlikely that Italy will meet the international target of 0.7 per cent of gross national income (GNI) allocated to ODA (with around 0.28 per cent ODA/GNI allocated in 2024).[9]

Second, the Steering Committee worked closely with the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Italian Agency for Cooperation (AICS), the Italian embassies in Africa, NGOs and the private sector in the organisation of “System’s Missions” to Africa. All actors involved have acknowledged an unprecedented level of coordination and a positive systemic shift that is also sending a strong message to the country offices of international finance institutions like the World Bank. These missions have been instrumental in collecting the needs of both Italian and African small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), while showing African communities and diasporas that the time is ripe to change the old narrative of Africa as a mere ‘recipient’ of aid, but rather as a solid business partner. In this process, the pragmatic decision not to ‘reinvent the wheel’ with smaller and scattered projects but rather to seek to maximise existing projects, leveraging on the expertise of private and non-profit actors, was a wise choice.

Third, the Plan is contributing to expanding the capacity of Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP) to become a stronger public development bank, getting it closer and closer to its European counterparts with much stronger and well-established development cooperation portfolios such as the Agence Française de Developpement or the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau. By managing the National Climate Fund, the Rotational Fund and issuing interest-bearing postal savings bonds and postal savings passbooks with an Italian State-backed guarantee (though these are still hard to mobilise to support international cooperation objectives), CDP plays a central role in the implementation of the Mattei Plan alone or in partnership with national and international partners. As an example, CDP and the African Development Bank (AfDB) jointly established the Growth and Resilience Platform for Africa (GRAf), committing up to 400 million euros over five years, with the aim of channelling funds through private equity and venture capital funds targeting high-impact areas like food security, local SMEs growth, and sustainable infrastructure. Moreover, CDP provided a 250 million euro ten-year term loan to the Africa Finance Corporation, backed by SACE, specifically to fund infrastructure projects like the Lobito Railway Corridor.[10] SACE will issue guarantees that cover up to 80 per cent or more of the financing for projects involving Italian companies, reducing the risk for commercial banks and unlocking capital that would otherwise be held back. These guarantees by SACE, which has announced over 2 billion euros in guarantees since 2024, are essential to make the African investment landscape more palatable for Italian SMEs.[11]

Finally, the Plan has undoubtedly created important synergies with other existing international initiatives, which have a stronger financial firepower. Among them, the Plan has formalised a solid alignment with the EU’s Global Gateway. This synergy can not only maximise Italy’s financial leverage but, most importantly, ensure that the Mattei Plan is not an isolated initiative, thereby increasing its long-term viability and international credibility. There are also geopolitical and geoeconomic reasons for this decision, as by presenting itself as the leading voice and architect of a “new” EU-Africa partnership, Italy seeks to reposition itself within the EU, asserting its national interests within a continental framework. In addition to the EU, the Mattei Plan has sealed important deals with multilateral development banks, which can ensure a more effective impact and the decision to increase its contribution to the three-year refinancing of the IDA (World Bank Group) by approximately 25 per cent, allocating 733 million euros,[12] is a truly significant signal and goes against the trend of other traditional donor countries.

Areas for improvement

Despite the progress, the Mattei Plan is also facing a series of critical structural and political challenges. Addressing them is important as Italy prepares to host the second Africa summit in the first semester of 2026. Five key challenges can be identified. First, while the Plan claims to have a “medium-to-long term” perspective, the focus so far risks remaining too linked to short-term deliverables that can bring immediate and more visible results. Considering that the financial mechanisms created are gaining more and more solidity, and that the Plan has generated important expectations from African partners, it is important that the Presidency of the Council of Ministers assigns it at least a ten-year lifespan, as well as a clear, multi-annual operational roadmap. This would seal it from electoral cycles, foster genuinely strategic partnerships with African and international partners, and bring change in sectors (e.g. education or capacity building) that require more time to deliver results. Co-designing projects in these areas is very complex, as it needs constant political and financial investment from the Government, the Embassies, CDP and AICS offices on the ground to build and consolidate trust and cope with local resistances or limited buy-in from the part of African Ministries or regional authorities.

Second, business actors are calling for a faster financial governance to speed up their investments and to preserve the high level of trust that Italy is currently benefiting from African partners. Several businesses still struggle to deal with some key barriers, such as the tax and import permits, suggesting a stronger role for the Steering Committee in tackling this regulatory uncertainty and facilitating bilateral agreements with African countries. In addition, private companies are also concerned about the clarity of procedures for engagement and the lack of transparent, accessible information on the resources available and the status of the implemented projects. A qualitative leap would be the creation of an online platform in three languages, easily accessible and with clear rules to all those profit and non-profit actors interested in taking part in the Plan, for instance, drawing on similar examples by Invitalia or the GSE platform for energy transition initiatives.

Third, despite having a privileged and open channel of communication with the Steering Committee, African diasporas complain that they are not yet official members of the Steering Committee. This risks excluding key actors from the project-design phase and generating an excessively top-down process that undermines the narrative of ‘co-creation’ and true African ownership. For this reason, it would be important for the Government to designate some diaspora representatives as fully-fledged members of the Steering Committee.

Fourth, while the Plan has had the merit to catalyse the interest of the private sector, so far it looks too focused on the needs of big industrial conglomerates, which do not really need public guarantees to invest in Africa. While it is not an easy task to reverse the traditional reluctance of Italian SMEs to work in Africa, especially in high-risk sectors like agriculture,[13] more efforts should be made to provide risk mitigation and knowledge support for Italian and African SMEs that are the real drivers of job creation and local value addition. In this sense, the Steering Committee should also play a bigger role in supporting the private sector that wants to invest in those middle-income countries in Africa (e.g. Senegal) that are facing financial distress and where rigid financial international rules make it hard to bring investments.

Finally, several NGOs warn that this business-oriented approach of the Mattei Plan prioritises countries with lower political and economic risk, potentially excluding low-income countries and fragile states. Bringing private investment to these countries is complex and requires stronger public guarantees and de-risking capital than currently dedicated,[14] or the Plan risks exacerbating regional development imbalances. In this sense, the commercial focus of the Plan must not overshadow the necessity of ODA in fragile contexts, such as countries affected by conflict or climate vulnerability. In these countries, ODA remains essential to support public goods and basic services (health, education, water) and institutional capacity building, areas where the profit motive is inadequate.

Broader implications for Italy’s development cooperation policy

The Mattei Plan has brought Africa back as a top priority of Italy’s foreign policy. Despite political claims, the continent has been absent for too many years in Italy’s external action. The Plan has the potential to strengthen Italy’s development and international partnership cooperation policy eleven years after the approval of Law 125/2014, as it represents a paradigm shift with four major profound implications. First, the Plan is leading to a very rapid centralisation of aid, moving development aid from being primarily the domain of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and AICS to a whole-of-government, strategic and high-level political priority. This centralisation can help overcome the historical fragmentation and lack of coordination of the Italian ODA, creating a single, coherent Italian voice and strategic direction in Africa. However, this high level of political investment must be accompanied by proper financial resources, and any ODA cuts in the 2026 Budget Law would go in the opposite direction.[15]

Second, the Mattei Plan shows a clear move from aid to partnership. Instead of being the primary source of funding, ODA (i.e. grants and concessional loans) is now viewed as the catalytic tool used to de-risk projects and crowd in private investment. The Plan elevates the Italian private sector as the engine of development cooperation, a dramatic shift from the past, when development cooperation heavily relied on civil society organisations and NGOs as the key implementers of ODA, by placing major Italian corporations and financial institutions at the forefront.

Third, the Plan explicitly integrates development with Italy’s core strategic interests, in particular energy security and the control of the root causes of migration. Yet, this integration carries the risk of being seen as purely prioritising Italian geopolitical needs over the autonomous development priorities of African nations, at the expense of the “non-predatory” narrative. Although bringing economic prosperity and industrialisation is essential to address Sub-Saharan job creation challenges, such a “root causes” strategy can lead to a highly transactional diplomacy where aid is conditional on migration control, diverting focus from comprehensive, democratic governance and human rights.

Finally, despite the anti-European stances and clichés, the Mattei Plan clearly shows a deep investment in stronger European and multilateral alignment, forcing the country to actively seek synergy with the EU’s Global Gateway and significantly increasing Italy’s engagement within the ‘Team Europe’ approach in Africa. In addition, the Plan is based on a solid commitment to working with major multilateral financial institutions, particularly the AfDB, positioning it as the main strategic financial partner for the Plan’s implementation. On the one hand, the “internationalisation” of the Mattei Plan within broader European initiatives is a realistic acknowledgement of the Plan’s limited financial envelope for a continental plan. On the other hand, this approach can also help Italy to carve out a distinct strategic role in Africa, in a context where the reputation of some European countries is undeniably highly contested.

Concrete policy recommendations in view of the second Italy-Africa Summit

The Mattei Plan has already a deep impact on Italy’s development cooperation approach to Africa, from a low-profile, fragmented, aid-focused function into a high-level, strategically centralised, blended finance initiative geared toward mutually beneficial economic and geopolitical outcomes. The 2026 Italy-Africa Summit will be a key moment to assess the level of progress achieved so far and to pivot from articulation to accelerated execution and inclusive governance to solidify the Plan’s long-term credibility. In view of the summit, five main policy recommendations can be outlined:

• Establish a centralised, publicly accessible digital platform (in English, French and Italian) detailing the implementation status, financing sources (ODA and private), local partners and measurable key performance indicators (KPIs) for every single project.

• Dedicate a minimum share (e.g. 20 per cent) of the 5.5 billion euro financial envelope to specialised financial products (e.g. first-loss guarantees, technical assistance grants) managed by CDP, SACE and AfDB, specifically tailored to lower the entry barrier for Italian and African SMEs and to facilitate diaspora investment.

• Create a Regulatory Streamlining Task Force within the Steering Committee with the specific mandate to identify and remove regulatory bottlenecks impeding the swift deployment of Italian and African resources (e.g. procurement rules, co-financing agreement standardisation).

• Ring-fence a dedicated portion of the ODA and Climate Fund resources to target least developed countries exclusively. These funds should prioritise grants for social infrastructure, basic services and climate adaptation (water, agroecology), where market mechanisms are not yet viable, ensuring the Plan is not solely transactional.

• Formalise the inclusion of African civil society leaders and diaspora representatives, as fully-fledged members of the Steering Committee.

Daniele Fattibene is Associate Fellow at IAI and Coordinator of the European Think Tanks Group (ETTG).

The author would like to acknowledge all those who took part in the closed-door round table titled “Il Piano Mattei per l’Africa: stato dell’arte, sinergie e prospettive future”, organised by IAI on 12 November 2025.

[1] Jaldi, Abdessalam and Alessandro Cercaci, “The Mattei Plan: Recasting Cooperation Through Strategy and Branding”, in PCNS Policy Briefs, No. 38/25 (August, 2025), https://www.policycenter.ma/node/9670.

[2] Italian Government, The Six Pillars of the Mattei Plan, 15 March 2024, https://www.governo.it/sites/governo.it/files/Italia-Africa_MatteiPlan_6pillars.pdf.

[3] Italian Government, Piano Mattei per l’Africa. Relazione annuale al Parlamento sullo stato di attuazione, 30 June 2025, https://www.governo.it/sites/governo.it/files/documenti/documenti/Notizie-allegati/Piano%20Mattei/Relazione_Attuazione_PianoMattei_2025.pdf.

[4] Rossi, Emanuele, “The Mattei Plan in 2025: Strategic Depth and Evolving Implementation”, in Decode 39, 18 July 2025, https://decode39.com/?p=11318.

[5] Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Three-year Programming and Policy Planning Document 2024-2026, June 2025, p. 17-18, https://www.esteri.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Three-year-Programming_Policy-Planning-Document_PPPD_2024-2026.pdf.

[6] Caballero-Vélez, Diego and Filippo Simonelli, “Good Intentions in Need of Good Governance: The Unclear State of the Mattei Plan”, in IAI Commentaries, No. 25/47 (July 2025), https://www.iai.it/en/node/20414.

[7] Italian Government, The Mattei Plan for Africa and the Global Gateway: A Common Effort with the African Continent, 20 June 2025, https://www.governo.it/en/node/29040.

[8] European Commission and Italian Government, Joint Press Release by the European Commission and the Presidency of the Council of Ministers of Italy, 20 June 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_25_1582.

[9] OECD, Development Co-operation Profiles: Italy, 11 June 2025, https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/development-co-operation-profiles_04b376d7-en/italy_53431c59-en.html.

[10] SACE, Cassa Depositi e Prestiti and SACE Provide EUR250 Million to Africa Finance Corporation, 20 June 2025, https://www.sace.it/en/media/press-releases-and-news/press-releases-details/cassa-depositi-e-prestiti-sace-and-africa-finance-corporation.

[11] SACE, SACE and the Mattei Plan, 7 July 2025, https://www.sace.it/en/media/press-releases-and-news/news-details/sace-and-the-mattei-plan.

[12] World Bank, Italy Increases IDA Commitment, Launches Africa Partnership with World Bank, 24 April 2025, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2025/04/24/-italy-increases-ida-commitment-launches-africa-partnership-with-world-bank.

[13] AGRA et al., 2022 Africa Agribusiness Outlook. Making Africa an Even Better Place to Do Agribusiness, March 2022, https://kpmg.com/ke/en/home/insights/2022/03/2022-africa-agribusiness-outlook.html.

[14] Desmidt, Sophie eta l., “Staying Engaged as Team Europe in Fragile Settings”, in ETTG Collective Reports, No. 3/2024 (December 2024), https://ettg.eu/team-europe-fragile-settings.

[15] “Legge di Bilancio 2026: le ONG chiedono al Parlamento di scongiurare i tagli alla cooperazione”, in Info cooperazione, 6 November 2025, https://www.info-cooperazione.it/?p=47125.