Titolo completo

The Lobito Corridor and Africa’s Development Agenda: Synergies with the Mattei Plan and Global Gateway

|

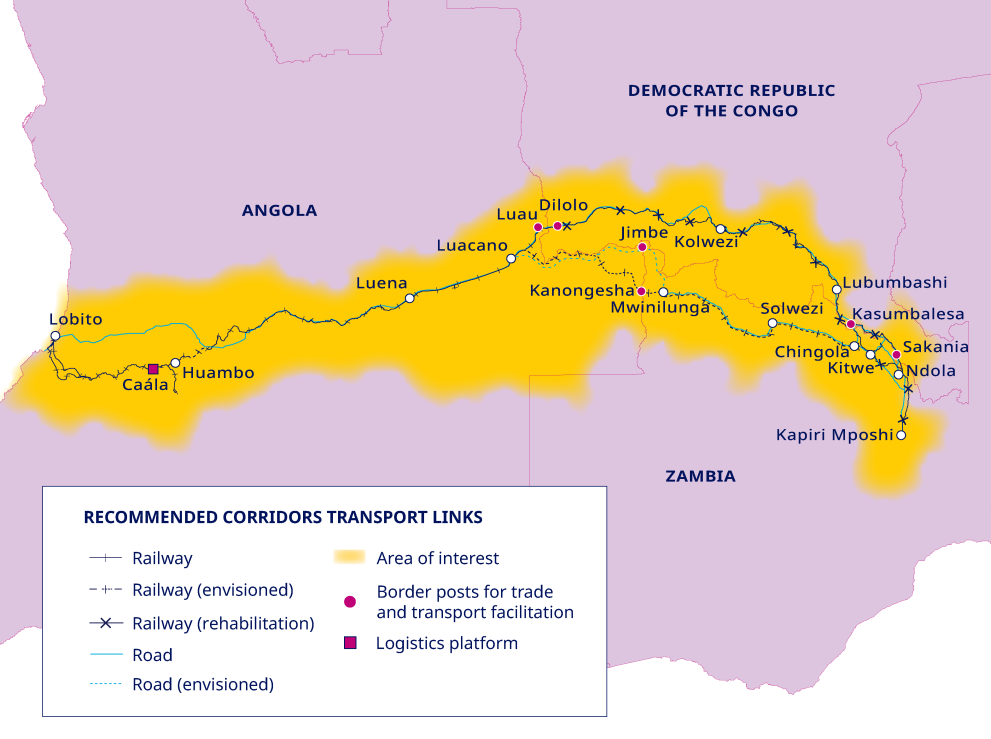

Positioned as southern Africa’s gateway to global trade and international markets, the Lobito Corridor spans approximately 1,300 km, extending from the Atlantic Ocean port city of Lobito in Angola through the country’s central highlands to the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Zambia (see Figure 1). The corridor connects the mineral-rich regions of the DRC and Zambia’s Copperbelt to the Atlantic Ocean via Angola’s Lobito Port. Owing to its strategic location, the corridor is attracting significant attention from neighbouring and investor countries alike, as well as international businesses linked to the regional mining industry.

Recognising its potential to revitalise trade, regional industrialisation and regional integration, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) designated the corridor a regional priority infrastructure project in its Regional Infrastructure Development Master Plan.[1] A global surge in demand for critical minerals located around the corridor, such as copper, lithium, nickel and cobalt, is fuelling interest in the project, and with it a multiplicity of actors seeking to secure fast and cheap access to critical and rare earth minerals.

At the regional level, investments in the corridor are expected to facilitate growth of regional value-chains anchored on critical minerals, agriculture and energy resources in Angola, DRC, Zambia and neighbouring countries. Additionally, infrastructure upgrades and modernisation of the corridor are expected to significantly improve transport efficiency, reducing both the time and cost of moving goods to coastal ports. At the local level, infrastructure development is expected to facilitate informal cross-border trade, re-establish commercial links between urban and rural areas, enhance livelihoods, create employment and improve food security for communities along the corridor. However, the implementation of this major infrastructure project also raises several concerns, most notably around financial transparency, adherence to environmental and human rights standards, and regulatory and harmonisation challenges.

Why does the Lobito Corridor matter?

Developed in 1902 as a colonial trade corridor to extract raw minerals from African hinterlands to international markets in Europe and the Americas, the Lobito Corridor today sits uneasily at the intersection of a global green transition, geopolitical contestation, poor regional infrastructure and governance deficits. Decades of civil strife in post-colonial Angola severely damaged infrastructure and slowed progress on upgrades and modernisation works on the corridor. By the time the civil war ended in 2002, only 34 km, less than 3 per cent of the rail along Angola’s coast, remained functional.[2] Between 2004 and 2014, the Chinese renovated parts of the corridor with a 1.2 billion US dollar “oil-for-infrastructure” loan. Renovation plans included upgrading and redesigning the railway to accommodate up to 67 stations and trains travelling up to 90 km/hr. The goal was for the rail to be able to carry up to 20 million tonnes of cargo and four million passengers per year.[3] However, this target has not been achieved yet. In 2024, the railway line carried fewer than 200,000 tonnes of cargo with a projected capacity of 750,000 tonnes by 2027.[4]

Figure 1 | Visual map of the Lobito Corridor

Source: European Commission DG for International Partnerships website: Lobito Corridor, https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/node/4522_en.

Today, the Lobito Corridor is partially operational and is one of the five major trade, transit and development routes in southern Africa. The development of the corridor is expected to significantly improve transport efficiency, reducing both the time and cost of moving goods and freight to coastal ports. It is also expected to create economic and livelihood opportunities for communities living along the corridor through facilitating access to markets for farmers and agri-producers, artisanal and small-scale miners and informal cross-border traders. According to Angola’s Census report, nearly a quarter of the country’s population lives in the four provinces covered by the Lobito Corridor, making its development a major national priority.[5] At the regional level, the corridor is expected to enhance regional trade and integration, aligning with the African Union’s vision of an integrated continent, providing a critical anchor to the roll-out of key African flagship projects like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

While the project’s significance cannot be overstated, its implementation creates additional structural and policy challenges. Realisation of cross-border infrastructure projects of this magnitude and size often poses several challenges, including regulatory and policy hurdles stemming from tensions between different legal regimes and frameworks on mining and land tenure systems, compensation mechanisms and environmental protection standards.

Regional drivers and dynamics

The Lobito Corridor project unfolds in a complex geopolitical context. For instance, 2025 saw conflict escalation between the DRC and Rwanda following failed peace talks in December 2024. Recent reports from humanitarian and aid organisations show that more than 7 million people have been displaced, both internally and externally.[6] The presence of Rwanda-backed M23 rebels in the eastern parts of the country and their advance southwards have raised fears of a regional conflict with spillover effects. A fragile, Trump-backed “minerals-for-peace” deal involving Kinshasa, Kigali and Washington has sought to put an end to the conflict. The widely criticised Trump peace deal was immediately followed by a US-DRC agreement to strengthen partnerships in DRC’s mining sector to enhance commercialisation of critical minerals considered necessary for the US interests and its National Security Strategy.[7]

The intersection of security, geopolitical and commercial interests in the Lobito Corridor and by extension in the Great Lakes region calls for a multilayered and multifaceted strategy to manage conflicting and sometimes overlapping interests among different actors. For instance, following conflict flare-ups in the eastern DRC, in February 2025, the European Parliament called on the Commission to sanction Rwanda by freezing direct budgetary support for Rwanda and to suspend a memorandum of understanding (MOU) on critical minerals signed between the EU and Kigali.[8] Calls for suspension of EU support to Kigali followed accusations by Congolese activists of EU complicity and complacency in the conflict. The EU’s position on this is further complicated by geopolitical considerations surrounding the DRC’s critical minerals and its supply chains.[9] For now, the deal has been placed under review in addition to sanctions introduced against some leaders of M23 and the Rwanda Defence Force.[10]

The economic conditions in the region also demand an analysis. Angola, a leading actor in the project, faces elevated sovereign risk. This raises concern about its debt sustainability and its ability to attract additional private investment. Additionally, Angola’s development model, characterised by infrastructure-for-oil loans, has been criticised as unsustainable, particularly on the back of falling oil prices, with further risks of debt default.[11] In the short-term, government efforts to diversify investors and markets have seen some success, with Angola’s public debt levels showing some improvement. In neighbouring Zambia which faced a risk default in 2020, debt sustainability has improved although the country faces additional structural challenges including frequent power blackouts and high electricity tariffs as a result of low power generation and climate-induced droughts. Lusaka is focusing on diversifying its energy mix by reducing reliance on hydropower. Already, Zambia is facing elevated ecological threats and environmental damage from contamination and toxic spills from a Chinese-owned mining enterprise.[12]

Informal cross-border trade

Infrastructure development along the corridor will enhance the capacity of the region to bolster agricultural value chains. This will allow participating countries to access international markets, build a skills base, foster technology transfer and create employment for millions of young people. In addition to developing infrastructure and agriculture, the Lobito Corridor is also expected to facilitate informal cross-border trade. Its realisation will reshape informal economies of extraction, trade and conflict geographies. The informal sector is a critical engine driving economic resilience in the region. It currently contributes between 30-40 per cent of total intra-regional trade.[13] The Lobito Corridor will facilitate an easy flow of goods, services and people across borders, thereby strengthening intra-regional trade in southern Africa, which stood at 41.4 per cent in 2024, the highest level on the continent.[14]

While formal corridor development focuses primarily on infrastructure, logistics and trade facilitation, the informal economy remains the social and economic lifeblood of border communities. Informal cross-border trading is mainly managed by women, accounting for 60-70 per cent of it. Recognising and integrating informal cross-border trade into corridor development plans will therefore strengthen Africa’s broader regional integration agenda. In fact, owing to its scale and dynamism, informal cross-border trade is driving what many describe as the real yet invisible integration of African economies, helping to advance regional connectivity and market integration in areas where formal initiatives remain slow and constrained by structural, institutional and policy barriers. Facilitating standardised regulatory environments underpinned by harmonised regional policy instruments will enable states to strike a balance between regulatory reform on one hand and their obligations to safeguard national security and combat transnational criminality on the other without undermining regional integration.

International interest in the corridor

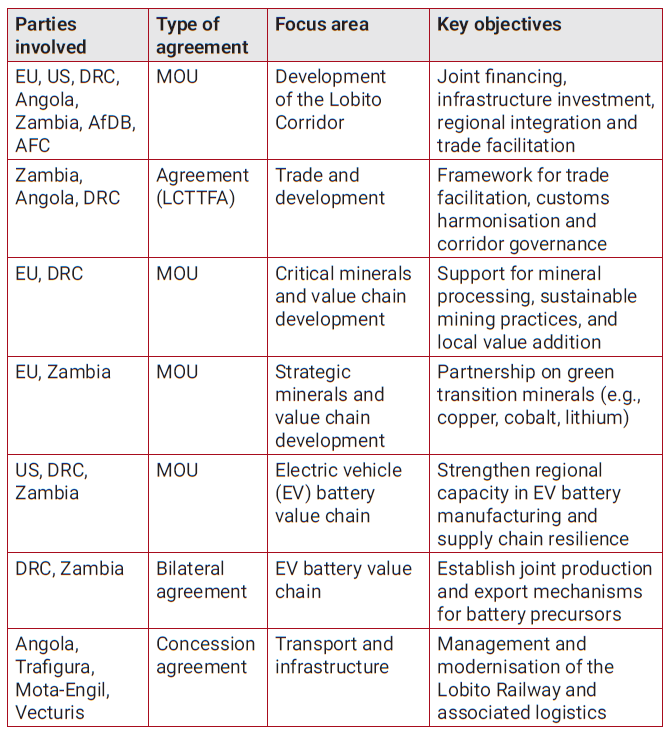

A global decarbonisation agenda and the rapid growth of the electric vehicle (EV) industry have intensified interest in the corridor, driving a surge in investments and attracting an increasing number of actors seeking opportunities in the region. The governments of the DRC and Zambia have signed several MOUs and agreements for infrastructure development to revitalise the corridor (see Table 1).

With the support and coordination of the SADC Secretariat, the three governments involved in the development of the corridor signed the Lobito Corridor Transit Transportation Facilitation Agency Agreement in Angola in January 2023. The agreement calls for a harmonisation of the national regulations and development strategies among the three participating countries.

Several financiers are involved in the financing of the Lobito Corridor project. For example, through the African Finance Corporation (AFC), the US allocated 1 billion US dollars to build and improve the railway of the corridor up to Zambia. The US, EU, AfDB and the AFC signed the Lobito Corridor Extension MOU to cooperate under the shared vision of the corridor, signalling growing interest by international actors to revive the corridor as a key economic artery in the region. AfDB estimates that 1.6 billion US dollars is required for the extension work and has itself committed 500,000 dollars to the project and has pledged to lead fundraising efforts to meet the investment needed.

A joint venture between Trafigura, Mota-Engil and Vecturis SA under the Lobito Atlantic Railway Company secured a 30-year concession in July 2023 to provide railway services on the condition that the company invests 450 million US dollars in Angola, and another 100 million dollars in the DRC. The company also secured a concession extendable for an additional 20-50 years on condition that the consortium builds a branch line connecting Luacano and Jimbe with a total length of 259 km, with an estimated cost of 1 billion dollars.[15]

Table 1 | MOUs and agreements linked to the Lobito Corridor

Navigating the geopolitics of the Lobito Corridor

The presence of Chinese firms and investments in the region, along with those from the EU, the US, Russia, Türkiye, India and others, is already visible, demonstrating not just the politics of minerals and mineral supply chains but also the geopolitics of infrastructure.

Africa currently needs up to 130-170 billion US dollars of investments annually to bridge its growing infrastructure gap.[16] Today, Chinese companies are involved in around 30 per cent of major infrastructure projects in Africa, both in the construction and as financiers.[17] With up to 2.6 billion US dollars required for infrastructure development in the Lobito Corridor, concerns around transparency have been raised over the financing of various aspects of the project, where most of the EU’s financing is private-sector led and implemented. China has committed 1.4 billion US dollars in refurbishing and modernising the Tanzania-Zambia railway (TAZARA) to facilitate the export of critical minerals through the Indian Ocean. While these two mega-infrastructure projects may appear to operate independently, both are critical to advancing the region and Africa’s long-term development objectives by plugging infrastructure gaps, attracting much-needed investments and unlocking economic opportunities that create jobs and improve livelihoods for ordinary people.[18]

The Lobito Corridor is not just a bet for international investors, it attests to a confidence in Africa’s future and will require African governments to overcome structural and policy bottlenecks, including possible tensions, such as those shown between Tanzania and Zambia in the case of the TAZARA corridor.[19] For the African continent, both the Lobito and TAZARA projects are a culmination of Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda’s vision of an integrated and prosperous continent.[20]

African development priorities, expressed through African Union frameworks, such as the African Green Minerals Strategy (AGMS) and the African Mining Vision (AMV) should guide European investments in the Lobito Corridor. Its transformative promise will only be realised if the project is designed and governed in ways that directly confront, rather than reproduce, the deep structural legacies of neo-colonialism that continue to shape the political economy of the region. In fragile contexts, large-scale infrastructure projects such as the Lobito Corridor also carry the risk that domestic budgets may be diverted towards providing security and protection for international investments, thereby undermining their intended development impact. For sustained impact, foreign and EU investments should be anchored on the development needs of local communities.

This requires that local and international actors involved in the project engage meaningfully with complex governance and sociopolitical realities that shape extraction and development in fragile contexts. It also demands commitment to shared good governance practices that strengthen resource-sharing partnerships and expand cross-border collaboration and coordination, enabling conditions for deeper economic and political integration to emerge. This encompasses creating a robust legal environment and strong monitoring mechanisms to ensure that investments do not cause harm or exacerbate existing tensions and grievances. More crucially, in a geopolitical context characterised by global geoeconomic and political competition, simply building infrastructure is not enough. Investments like the Lobito Corridor must be accompanied by the commitment to transform the lives of communities through supporting local industrialisation, job creation and value addition at source.

Marianna Lunardini is a Research Fellow in the ‘Multilateralism and global governance’ programme at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI). Darlington Tshuma is a Research Fellow with the ‘Mediterranean, Middle East and Africa’ programme at IAI.

This brief was produced in the framework of the research project “Italy at the forefront of infrastructure diplomacy: the Lobito Corridor case”, conducted by IAI with the support of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo and Fondazione CSF. All opinions expressed in this document are solely and exclusively those of the author.

[1] SADC, Regional Infrastructure Development Master Plan. Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) Sector Plan, August 2012, https://www.sadc.int/node/1862.

[2] Duarte, Ana et al., “Diversification and Development, or ‘White Elephants’? Transport in Angola’s Lobito Corridor”, in CMI Reports, No. 2015/7 (April 2015), https://www.cmi.no/publications/5510.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Diallo, Fatoumata, “Lobito Will Be Six Times Faster than Other Corridors,’ CEO Fournier Says”, in The Africa Report, 27 August 2025, https://www.theafricareport.com/390905/lobito-will-be-six-times-faster-than-other-corridors-ceo-fournier-says.

[5] Angola National Institute of Statistics (INE), Resultados definitivos recenseamento geral da população e habitação RGPH-2024, November 2025, https://www.ine.gov.ao/publicacoes/detalhes/NDc0MTE%3D.

[6] OHCHR, Democratic Republic of the Congo: National Ownership Essential to Address Internal Displacement Crisis, Says UN Expert, 2 June 2025, https://www.ohchr.org/en/node/111750.

[7] US, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, November 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/2025-National-Security-Strategy.pdf.

[8] European Parliament, MEPs Want to Suspend EU-Rwanda Deal on Sustainable Value Chains for Critical Raw Materials, 13 February 2025, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20250206IPR26752.

[9] Châtelot, Christophe, “DRC Foreign Minister: ‘The European Union Is Complicit in the Plundering of Our Resources and the Aggression of Rwanda’”, in Le Monde, 29 February 2024, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/le-monde-africa/article/2024/02/29/drc-the-european-union-is-complicit-in-the-plundering-of-our-resources-and-the-aggression-of-rwanda_6570043_124.html.

[10] Karkare, Poorva and Bruce Byiers, “The Lobito Corridor: Between European Geopolitics and African Agency”, in ECDPM Papers, 16 April 2025, https://ecdpm.org/work/lobito-corridor-between-european-geopolitics-and-african-agency.

[11] Yushikawa, Sumie, “China and Angola: From the Pioneering ‘Angolan Model’ to a ‘New’ Relationship”, in Analysis from the East-West Center, Vol. 28, No. 170 (November 2024), https://www.eastwestcenter.org/node/106946.

[12] Gondwe, Kennedy, “Zambia Dismisses US Health Warning after Toxic Spill in Copper Mining Area”, in BBC News, 7 August 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cx2qeexv791o.

[13] Kodero, Cliff Ubba, “Development Without Borders? Informal Cross-Border Trade in Africa”, in The Palgrave Handbook of African Political Economy, Cham, Springer, 2020, p. 1051-1067.

[14] African Export-Import Bank, African Trade Report 2025, Cairo, Afreximbank, 2025, p. 63, https://www.afreximbank.com/reports/african-trade-report-2025.

[15] Zhang, Jing and Lingfei Weng, “Financing Railway Construction to Corridor Development amid Geopolitical Rivalry: Study Two Cases in Africa”, in CSST Working Papers, No. 12 (September 2025), p. 19, https://www.soas.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2025-09/WP%20012_Financing%20Railway%20Construction%20to%20Corridor%20Development%20amid%20Geopolitical%20Rivalry_1.pdf.

[16] Cilliers, Jakkie and Blessin Chipanda, “Large Infrastructure”, in ISS African Futures Themes, last updated 14 January 2025, https://futures.issafrica.org/thematic/11-large-infrastructure.

[17] Nantulya, Paul, “China’s Critical Mineral Strategy in Africa”, in African Center for Strategic Studies Spotlights, 9 December 2025, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/china-africa-critical-minerals.

[18] Kizito Sseruwagi, Nnanda, “China’s Role in the Lobito Corridor”, in DWC Foreign Policy Analysis, 19 October 2025, https://www.dwcug.org/?p=2400.

[19] Mbikusita-Lewanika, Akashambatwa and Solange Guo Chatelard, “Railroads and Rivalries in Southern Africa”, in The China in Africa Podcast, 27 September 2024, https://chinaglobalsouth.com/?p=46250.

[20] Devermont, Judd, “Two Railroads, One Vision”, in CSIS Commentaries, 10 October 2024, https://www.csis.org/node/112732.