Street Protests and Socio-Economic Challenges in Iran: The Case of Khuzestan Province

Street Protests and Socio-Economic Challenges in Iran: The Case of Khuzestan Province

Giorgia Perletta*

With the European Union struggling to prevent the collapse of the Iranian nuclear deal and as Washington and its allies seek to ramp-up economic pressure against Tehran, internal socio-economic and political trends in the country are emerging as the new battle ground in the decades-long struggle between Iran and its adversaries.

In late 2017, localized protests erupted in various Iranian cities, resulting in somewhat exaggerated media coverage in the West that seemed to point to an impeding popular revolution in Iran. Protests erupted in the north-eastern Khorasan province, in the holy city of Mashhad, from where they quickly spread to over 85 cities and provincial towns.[1]

Many observers concluded that former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and his allies were somehow involved in these protests, not least due to the similarity between the protesters demands and Ahmadinejad’s political rhetoric and support base. Others have questioned the involvement of Ahmadinejad,[2] but since the protests ended, sporadic demonstrations have continued in several cities and regions, including in Ahvaz, the regional capital of the Khuzestan province in south-western Iran, leading to severe crackdowns by the authorities.[3]

Protests against the central government have been a reoccurring trend in Khuzestan. For decades, the province represented a significant source of instability in the country, even when it enjoyed the status of a semi-autonomous “emirate” named “Arabistan” until 1925.

Dynamics in the province are different compared to other regions. Distinguishing factors include the mixed Arab and Persian population, energy and natural resource concentration and a complex history of relations with the central authorities in Tehran.

Other regions are also witnessing protests. One example is the south-eastern province of Sistan and Baluchestan, another area with a high-concentration of ethic minorities and a province that has long been a hotbed of activism against the central authorities. Bordering Pakistan and Afghanistan, this province suffers a lack of services and a severe drug trafficking problem. Further tensions stem from the resentment of the predominantly Sunni Balochi minority that inhabit the province. Baloch armed groups have engaged in a long insurgency campaign against the central authorities in both Iran and Pakistan, leading to a significant Iranian military presence in the province.[4]

The reoccurrence of protests in Iran, and particularly in the Khuzestan and Sistan and Baluchestan provinces, is often explained through the prism of religion, ethnicity and, in the former case, Arab-Persian tensions.

Such perspectives offer a somewhat simplistic analysis, however. Rather, socio-economic inequality, poverty and pollution (i.e. the infamous example of the Karun river crossing the Khuzestan province) and a shortage of health facilities, roads and infrastructure stand at the origin of popular grievances.[5] For example, recent protests in Khorramshahr, another city in Khuzestan province, were due to sever water contamination.[6]

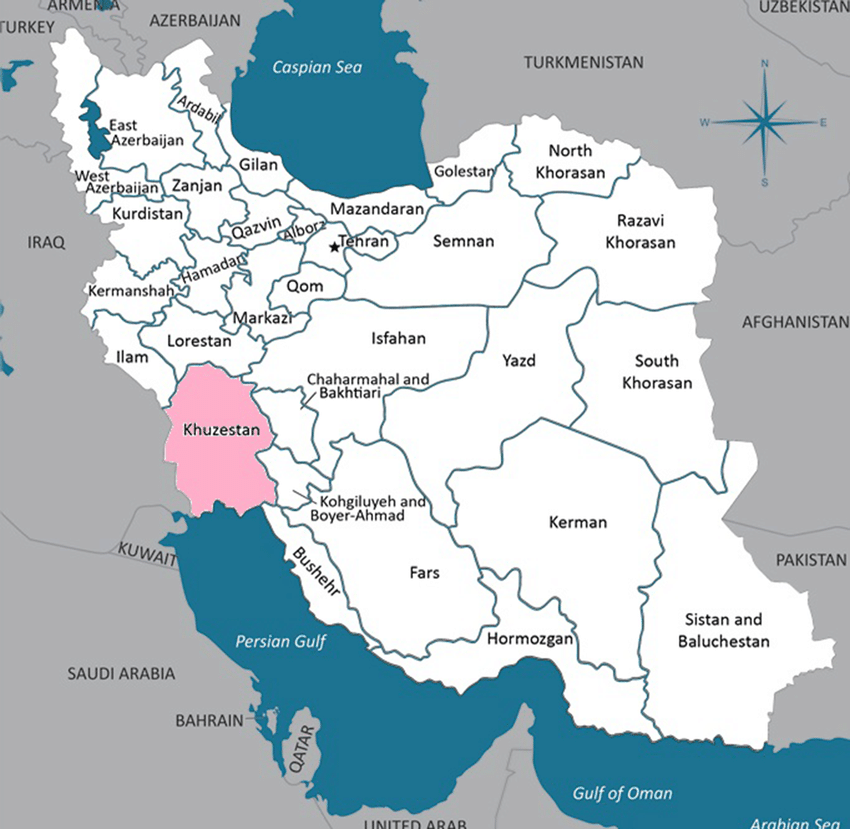

Figure 1 | Geographical location of Khuzestan province in Iran

Source: Mostafa Salehi-Vaziri et al., “An Outbreak of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever in the South West of Iran”, in Jundishapur Journal of Microbiology, Vol. 10, No. 1 (January 2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.5812/jjm.41735.

Khuzestan province enjoys the highest concentration of energy resources in Iran, with an estimated 85 per cent of oil reserves and 60 per cent of gas reserves.[7] Nonetheless, its residents, particularly the Iranian-Arab community, accounting for less than 2 per cent of the Iranian population (estimated at 80 million in 2016),[8] have long been subject to political, economic and social marginalization. Last April, Ahvaz witnessed further demonstrations, this time sparked by a controversial television programme described as discriminatory towards the ethnically Arab population of Iran.[9]

In 2016, Hassan Rouhani, President of the Islamic Republic of Iran, launched three oil development projects in collaboration with Chinese firms with the aim of improving oil production in the province.[10] Today, 350 thousand barrels of oil per day are being produced in the joint fields of West Karun and Azar.[11] Despite the promise of more equal development projects, living conditions have not improved and remain a source of popular discontent.

According to a 2011 census, unemployment reached 53 per cent in many towns of the area, making Khuzestan the province with the highest unemployment rate in Iran, followed by Sistan and Baluchestan.[12] While the unemployment rate has diminished recently according to government figures, Khuzestan is still among the five regions with the highest inactivity levels in the whole country.

In a very delicate phase for the Islamic Republic of Iran, considering the efforts of the US and its allies to weaken Iran’s economy, the reoccurrence of protests in Khuzestan and other regions could represent a significant risk for the system’s stability.

Provocative statements by Israel and Saudi Arabia, some of which are no doubt aimed at increasing tensions within Iran, have today married with the anti-Tehran obsessions of US neoconservatives in the Trump administration. The US’s unilateral withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal was followed by calls by Mike Pompeo, the US’s new Secretary of State, to impose the “strongest sanctions in history” on Iran.[13]

Pompeo’s speech included twelve demands that sound more like an “ultimatum” than a serious attempt at diplomacy. Iran has categorically refused the US diktat and is looking to Europe and other states to preserve the Iran nuclear deal and keep investments flowing.

The current political, military and economic pressure on Iran is indeed aimed at exploiting socio-economic challenges to exacerbate internal tensions. The reintroduction of sanctions could provoke a further crisis in Iran’s banking and commercial system, exacerbating the situation of unemployed youth, low-wage workers and subaltern classes. Washington and its allies are essentially engaged in economic warfare against Iran, seeking to prevent international actors from investing in the country or buying its oil as a means to collapse the regime from within.

In this scenario, popular protests could become more frequent to the point of undermining Rouhani’s government. Government efforts to promote economic development are dependent on the removal of sanctions and Iran’s gradual re-integration in the international economy. In this context, Iran must seek to better integrate outlaying regions and peripheries, limiting the existence of elements that can be exploited by external actors and regional adversaries.

Sanctions have proven ineffective in the past to change the posture of the Iranian government (and that of other countries). Instead, they have generally exacerbated internal tensions while worsening the daily lives of ordinary citizens.

Most importantly, during periods of isolation and closure, it was the conservative hardliners in Iran – the Islamic Revolutionary Guards in particular – that benefitted, as these actors control the black market and important elements of the economy in the country.[14]

Against this backdrop of heightening tensions and efforts to weaken the Iranian government from within, it will fall to Europe, and in particular the EU3+1 (Germany, France and the UK, plus the EU High Representative Federica Mogherini) to find creative means to keep the deal alive.

Important in this regard will be to devise a mechanism that will allow Iran to strengthen its economy, through investments and oil exports. Economic growth and opportunities in Iran represent the main avenue to guarantee political stability and avoid a return of more radical forces (such as the followers of the previous president, Ahmadinejad) that have traditionally gained the most from Iran’s international isolation.

Ultimately, sanctions and containment cannot be described as a recipe for regional stability. Rather, these will likely result in further chaos and instability, both in the unlikely event of a collapse of the Iranian regime, or in the eventuality that more hard-line forces return to power in Teheran.

Now is time to learn from history and devise a means to responsibly engage with Iran without falling prey to the errors of the past, particularly when it comes to the avoidance of abrupt – and often foreign imposed – changes to the political systems of Middle Eastern states.

* Giorgia Perletta is Ph.D. Candidate in Institutions and Policies within the Department of Political Science at the Catholic University of Milan.

[1] Asef Bayat, “The Fire That Fueled the Iran Protests”, in The Atlantic, 27 January 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/iran-protest-mashaad-green-class-labor-economy/551690.

[2] Giorgia Perletta, “How Recent Protests Could Revive Ahmadinejad’s Fortunes in Iran”, in IranSource, 18 June 2018, http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/how-recent-protests-could-revive-ahmadinejad-s-fortunes-in-iran.

[3] Ahmad Majidyar, “Iranian Arabs Stage Rallies in Khuzestan to Protest State-Sanctioned Discrimination”, in Iran Observed, 30 March 2018, https://www.mei.edu/node/57545.

[4] Nicholas Cappuccino, “Baluch Insurgents in Iran”, in The Iran Primer, 5 April 2017, http://iranprimer.usip.org/node/3931.

[5] “How Iran’s Khuzestan Went from Wetland to Wasteland”, in The Guardian Iran blog, 16 April 2015, https://gu.com/p/47fap.

[6] “Protest Over Water Scarcity Turns Violent In Southwestern Iran”, in RFE/RL’s Radio Farda, 1 July 2018, https://www.rferl.org/a/protest-over-water-scarcity-turns-violent-in-southwestern-iran/29330155.html.

[7] US Energy Information Administration (EIA), Country Analysis Brief: Iran, last updated 9 April 2018, https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/analysis.php?iso=IRN.

[8] Statistical Center of Iran, Census 2016 - General Results, https://www.amar.org.ir/english/Population-and-Housing-Censuses/Census-2016-General-Results.

[9] Saeid Jafari, “Iran’s TV Censors Draw Ridicule, Protests”, in Al-Monitor, 26 April 2018, http://almon.co/31fa.

[10] “3 Oil Projects Launched in Khuzestan Province”, in Financial Tribune, 14 November 2016, https://financialtribune.com/node/53546.

[11] “West Karoon, Azar Oilfields Yielding 350,000 b/d: PEDEC”, in Shana, 5 February 2018, https://www.shana.ir/en/newsagency/281253.

[12] “Which provinces in Iran, the 60% of their people are unemployed?” (in Farsi), in Tabnak, http://www.tabnak.ir/fa/news/735251.

[13] US Department of State, After the Deal: A New Iran Strategy, Remarks by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo at The Heritage Foundation, Washington, 21 May 2018, https://www.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2018/05/282301.htm.

[14] Nader Habibi, “Can Rouhani Revitalize Iran’s Oil and Gas Industry?”, in Middle East Briefs, No. 80 (June 2014), http://www.brandeis.edu/crown/publications/meb/meb80.html.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, July 2018, 5 p. -

In:

-

Issue

18|38