Public Opinion and Development Policy: Alignment Needed

The crises of the past few years have significantly affected the volumes of official development assistance (ODA) – also known as aid – provided by traditional donors. 2023 marked the fifth consecutive year for increased ODA allocations globally: total volumes reached 223.7 billion US dollars, a significant increase from the 160 billion US dollars provided in 2019. The succession of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine and, most recently, the flare-up of the Israel-Palestine conflict contributed to such increase.

Absolute volumes however position members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC), that is, traditional donors, still far away from the United Nations target of allocating 0.7 per cent of gross national income (GNI) to ODA – in 2023, the OECD average hovered around 0.37 per cent.[1] Although this percentage is the highest in 55 years,[2] the need for concessional finance for developing countries has arguably never been more urgent. The challenges brought about by an ever-worsening climate crisis, coupled with long-standing issues such as poverty and poor health are enough to justify increased ODA, according to practitioners.[3]

These figures are usually (and rightly) discussed from such outward impact perspective – how will a less generous donor affect the beneficiaries whose livelihoods its ODA supports? The input dimension, that is, whether these policies align with a country’s public sentiment on ODA, is however relatively less explored. ODA is public funding, so it might be legitimate to ask: where does public opinion stand on aid, and what could this possibly mean for development policy and practice?

Spending where the mind is?

Let’s zoom in on five traditional donor countries where public opinion surveys on development engagement were carried out in recent years – the United Kingdom, Germany, France, the United States and Italy.[4] These countries were among the top ten largest ODA providers in 2023 in absolute terms.[5]

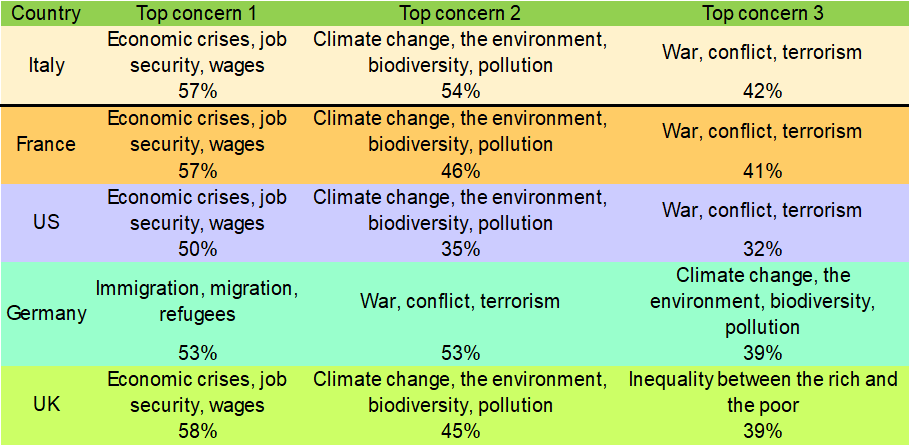

In the surveys, though to different extents, economic crises and climate change were mentioned among the top three most pressing issues in all the five surveyed countries, as illustrated in Figure 1. Only UK respondents mentioned inequality between the rich and the poor among their top concerns, although this might refer both to global inequalities and inequalities within UK society. The issue of education, healthcare, clean water and hunger in developing countries was generally less selected by respondents – 31 per cent of the sample in France, 28 per cent in the US, 18 per cent in Germany, 25 per cent in the UK, and 20 per cent in Italy.[6] On the other hand, war, conflict and terrorism were very much on people’s minds, the continued war in Ukraine being a potential explanation for this.[7]

Figure 1 | Top three main concerns in selected countries

Note: A line was added in this and subsequent figures reporting all country data to distinguish between Italy’s and other countries’ data, due to the different data collection and reporting methodologies mentioned above.

Source: Author’s elaboration on LAPS and IAI, Italians and Development Cooperation in 2023, cit.; Paolo Morini, DEL Dashboards, cit.

Interestingly, while ODA for Ukraine overall increased by 9 per cent in 2023, totalling 20 billion US dollars, only two of the five countries followed this upward trend in funding. Germany’s and the US’s ODA to Ukraine increased by 0.8 per cent and 2.7 per cent respectively. France, Italy and the UK, instead, allocated around 1 to 2 per cent less ODA to Ukraine in 2023[8] – although other, non-ODA type of aid (for example, military) was also provided to Ukraine by these countries.

Decreasing aid against public support for it

In terms of the actual level of ODA provided in 2023, the fact that economic crises were indicated as a top concern in all five countries might help to understand why reaching the 0.7 per cent ODA/GNI goal remains so elusive. Governments continue to face a challenging macroeconomic environment, especially in Europe, and need to balance domestic demands with international commitments. The Italian government, for example, made this point very clear when discussing the 2023 budget and related ODA allocations.[9] This may explain the -5.8 per cent and -15.5 per cent in Germany’s and Italy’s 2023 ODA, respectively, driven mostly by a drop in bilateral loans.[10] Similarly, France’s ODA recorded a -11 per cent. By contrast, the UK and the US increased their 2023 ODA spending by 12.1 per cent and 5.2 per cent respectively.[11]

From the public opinion’s perspective, however, while economic crises were high on respondents’ minds and lowest-income countries’ development was less of a concern, the majority of respondents in all five countries expressed support for either stable or even increased levels of ODA spending. In Italy, 41 per cent of respondents were in favour of increased ODA, and 42 per cent supported constant levels. In Germany, 55 per cent supported either an increase or stable spending; this figure was 60 per cent in France, 56 per cent in the US, and 51 per cent in the UK. The 2023 German, French and Italian cuts therefore represent the largest discrepancy between policymaking and public sentiment, even though the policy decisions behind them likely share the same preoccupation with domestic economic woes as the public’s.

Effective ODA channels

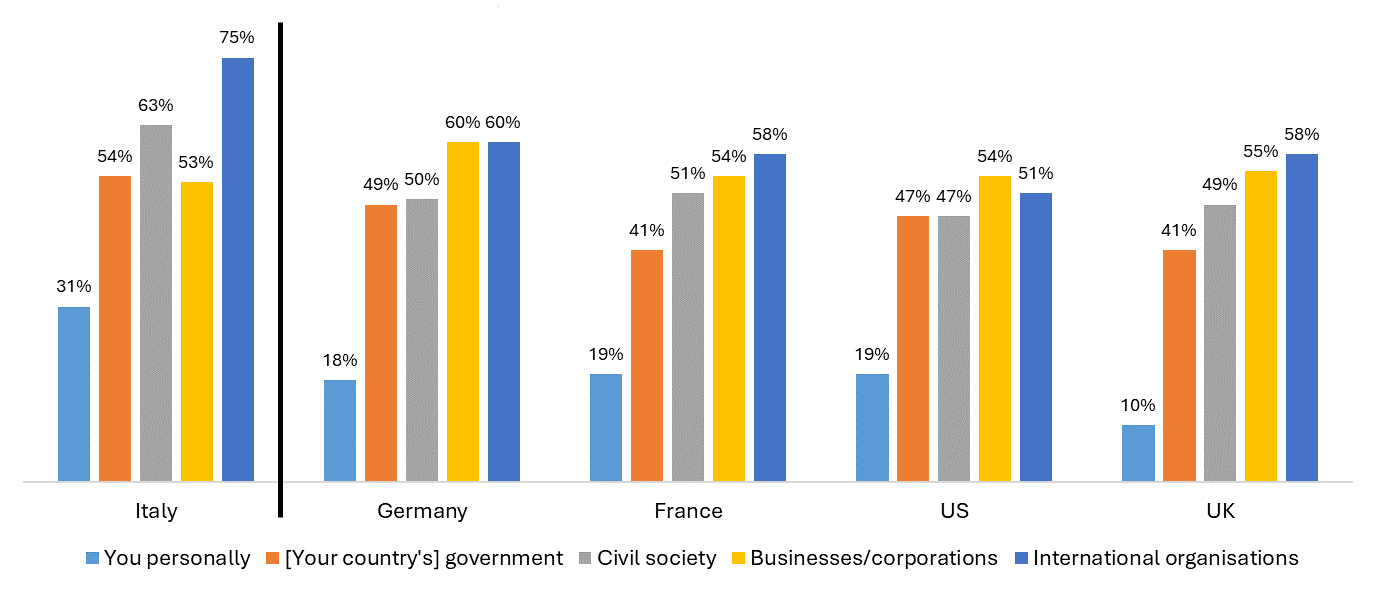

As far as aid channels are concerned, respondents in the five analysed countries were asked to indicate the impact that certain development actors have on poverty reduction. As Figure 2 illustrates, individual actions were deemed the least impactful by all respondents; on the other hand, with the exception of the US, international organisations were considered to have the highest potential for poverty reduction. Governments, instead, came fourth on the impact scale, following the private sector and civil society organisations.

Figure 2 | Percentage of respondents who attributed high potential impact for poverty reduction to these development actors

Source: Author’s elaboration on LAPS and IAI, Italians and Development Cooperation in 2023, cit.; Paolo Morini, DEL Dashboards, cit.

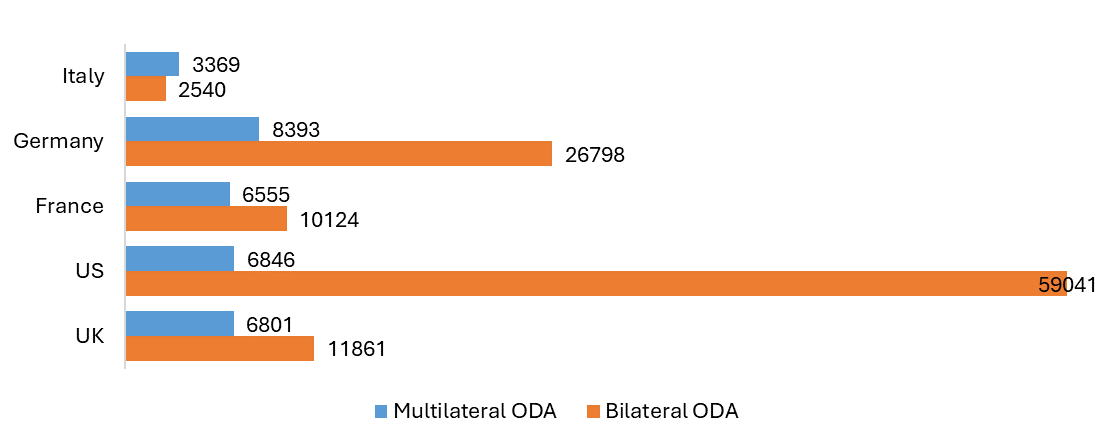

This is another area where policymaking and public opinion seem to differ. While international organisations are perceived as the most impactful, in 2023 the amount of aid that was channelled through them (multilateral ODA) was significantly lower than the aid directly provided by governments to partners (bilateral ODA). Figure 3 illustrates these proportions in the five analysed countries. With the exception of Italy,[12] bilateral ODA was higher than multilateral ODA. Therefore, there seems to be a disconnect between what people think and what policymakers decide.

Figure 3 | Amounts of ODA provided through multilateral and bilateral channels (million US dollars)

Author’s elaboration on OECD, ODA in 2023 Preliminary Data, v2, 12 April 2024, https://webfs.oecd.org/oda/DataCollection/Resources/2023-preliminary-dat....

It is however worth noting that for US citizens, the private sector is more impactful than international organisations and governments. Private finance is not always reflected by ODA data, making it difficult to determine whether public opinion and traditional donor’s finance is aligned in this regard. Nevertheless, looking at the most recent data for private flow disbursements, the US ranked first among the five analysed countries for amount of private finance provided to developing countries in 2022 – around 114.5 billion US dollars. Germany, where the private sector is considered as impactful as international organisations, came in second with 18 billion US dollars. France followed with 7 billion US dollars, while Italy, where business was considered the fourth most impactful, provided only 400 million US dollars. No data were available for the UK.[13] Although private financial flows are not necessarily a reflection of policy decisions, their amount, which at times is even higher than ODA, seems to partially reflect the public sentiment.

Inputs for G7 development policy action

ODA allocations are a national policy decision, and are not usually discussed in the G7 context beyond the renewed commitment to reach the 0.7 per cent ODA/GNI target.[14] Nevertheless, 76 per cent of ODA was provided by G7 donors in 2023; their collective decisions therefore significantly affect total aid flows. Based on the findings of the public opinion surveys conducted in Italy, France, Germany, the UK and the US, continued action to address ongoing conflicts is necessary, given the high levels of concern with wars in the public. Addressing the climate crisis is equally important; while it is not yet known how much funding went to this budget line in 2023, it is crucial that G7 countries continue being committed to decreasing emissions and facilitating adaptation, both domestically and internationally through climate finance.

More generally, while policymakers continue to face domestic economic challenges that reduce the likelihood of increasing aid budgets in the near future, the public support for stable or increased levels of ODA should be kept in mind. Thus, striving for the 0.7 per cent ODA/GNI goal remains a necessary pursuit.

As far as aid channels are concerned, international organisations are regarded by citizens as the most impactful. G7 governments could rebalance the proportion of bilateral versus multilateral ODA accordingly, increasing the share of the latter. Furthermore, the private sector could also be more greatly leveraged as a tool for poverty reduction. Joint commitments to strengthen the adoption of instruments to this end will be necessary to close the global income, infrastructure, energy and climate preparedness gaps that persist.

Irene Paviotti is a former Junior Researcher in the Multilateralism and Global Governance programme at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

[1] OECD, International Aid Rises in 2023 with Increased Support to Ukraine and Humanitarian Needs, 11 April 2024, https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/international-aid-rises-in-2023-with-increased-support-to-ukraine-and-humanitarian-needs.htm; OECD on Development, “Official Development Assistance (ODA) in 2023, by Members of the Development Assistance Committee (Preliminary Data)”, in ODA in 2023 - Preliminary Figures, 16 April 2024, https://public.flourish.studio/story/2315218.

[2] 1969 was last year the OECD average ODA/GNI percentage was 0.37 per cent. OECD on Development, “Official Development Assistance (ODA) in Historical Perspective: 1960-2023”, in ODA in 2023 - Preliminary Figures, 16 April 2024, https://public.flourish.studio/story/2315218.

[3] Concord Europe, ODA … Missing the Mark (Again): Preliminary 2023 Figures Show EU Aid Keeps Failing Human Development and Equality, 12 April 2024, https://wp.me/p76mJt-7iV.

[4] Public engagement on development issues was investigated across the UK, Germany, France and the US through a questionnaire developed by Development Engagement Lab (DEL). In the context of the project “A new agenda for development: the role of development cooperation in the Italian G7 Presidency”, IAI adapted its own questionnaire to align it with DEL’s. Data illustrated here refers to the October 2023 survey round for the UK, Germany, France and the US, and to the September 2023 IAI survey for Italy. Please note that while the questions asked were comparable, sample size differed between DEL and IAI’s surveys (6,000 < n < 8,000 in DEL’s surveys, versus n=1,026 in IAI’s), and responses were represented in slightly different ways. The results are therefore described here at a face value, and these methodological differences should be kept in mind before making any direct comparison.

[5] The United States was the largest donor (66 billion US dollars), followed by Germany (36 billion). The United Kingdom came in fifth with 19 billion US dollars, followed by France (15 billion). Italy ranked ninth with 6 billion US dollars. Source: OECD on Development, “Official Development Assistance (ODA) in 2023, by Members of the Development Assistance Committee (Preliminary Data)”, cit.

[6] For the full set of data see LAPS and IAI, Italians and Development Cooperation in 2023, Rome, IAI, December 2023, https://www.iai.it/en/node/17888; Paolo Morini, DEL France Dashboard October 2023, London, DEL, 2023, https://developmentcompass.org/publications/briefs-and-reports/france-dashboard-october-2023; Paolo Morini, DEL United States Dashboard October 2023, London, DEL, 2023, https://developmentcompass.org/publications/briefs-and-reports/united-states-dashboard-october-2023; Paolo Morini, DEL Germany Dashboard October 2023, London, DEL, 2023, https://developmentcompass.org/publications/briefs-and-reports/germany-dashboard-october-2023; Paolo Morini, DEL Great Britain Dashboard October 2023, London, DEL, 2023, https://developmentcompass.org/publications/briefs-and-reports/great-britain-dashboard-october-2023.

[7] The surveys were conducted before the flare-up in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

[8] OECD, ODA Levels in 2023 – Preliminary Data. Detailed Summary Note, 11 April 2024, https://www.oecd.org/dac/ODA-summary-2023.pdf.

[9] Italian Chamber of Deputies, Audizione del Ministro degli affari esteri e della cooperazione internazionale, On. Antonio Tajani, sulle linee programmatiche del suo Dicastero, 13 December 2022, http://documenti.camera.it/leg19/resoconti/commissioni/stenografici/pdf/03c03/audiz2/audizione/2022/12/13/leg.19.stencomm.data20221213.U1.com03c03.audiz2.audizione.0001.pdf.

[10] Despite these cuts, Germany was the only country of the five analysed here to reach the 0.7 per cent ODA/GNI goal in 2023. See OECD on Development, “Official Development Assistance (ODA) in 2023, by Members of the Development Assistance Committee (Preliminary Data)”, cit.

[11] OECD, ODA Levels in 2023 – Preliminary Data. Detailed Summary Note, cit.

[12] This unequal distribution between bilateral and multilateral ODA has long been lamented by practitioners as a missed opportunity to showcase the country’s active role in development cooperation. See Openpolis, La cooperazione allo sviluppo nella legge di bilancio, intervista a Ivana Borsotto, 20 January 2023, https://www.openpolis.it/la-cooperazione-allo-sviluppo-nella-legge-di-bilancio-intervista-a-ivana-borsotto.

[13] OECD QWIDS: Private Flows (Disbursements) in 2022: France, Germany, Italy, UK and US, https://stats.oecd.org/qwids/#?x=1&y=6&f=4:3,2:1,3:51,5:3,7:1&q=4:3+2:1+3:51+5:3+7:1+1:9,10,13,23,24+6:2022. For a definition of private flows, see OECD website: DAC Glossary of Key Terms and Concepts, https://www.oecd.org/dac/dac-glossary.htm.

[14] G7 Hiroshima Leaders’ Communiqué, 20 May 2023, http://www.g7.utoronto.ca/summit/2023hiroshima/230520-communique.html.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, April 2024, 6 p. -

In:

-

Issue

24|18