Titolo completo

Bridging the EU’s Innovation Gap: Supporting Hubs for Academic-Powered Enterprises

“It is […] essential to establish and consolidate European academic institutions at the forefront of global research.” (Mario Draghi)[1]

In the current geopolitical conditions, marked by a major war on the European continent and heightened global competition, Europe’s thirst for research and development should be apparent, yet a critical gap persists between academic breakthroughs and marketable applications. Despite a modest 0.6 per cent improvement in innovation performance between 2023 and 2024,[2] systemic barriers continue to impede effective technology transfer. The ambitious goals for 2030 set by the European Commission, such as becoming a global leader in strategic technologies, significantly increasing private-sector investment in research and development (R&D) and enhancing digital sovereignty,[3] remain unreachable, lacking a dedicated policy to bridge this gap.

This innovation shortfall undermines Europe’s global competitiveness compared to leaders such as the United States and the People’s Republic of China. Underinvestment in R&D, fragmented innovation ecosystems, regulatory complexities and insufficient venture capital collectively result in lower private sector engagement and fewer patents in strategic fields.[4] Injecting new fuel into Europe’s innovation engine is essential for generating disruptive, value-driven research.[5]

To address this gap, a targeted funding mechanism could be introduced, designed to empower existing university-led technology hubs. These hubs could then identify and nourish high-potential projects in their early stages, while in parallel redesigning the fund-of-funds mechanism prioritising regional development in order to tackle existing imbalances. This strategy could contribute to narrowing the gap between research and market, unleashing the currently chained potential of European innovation.

The limits of current policies

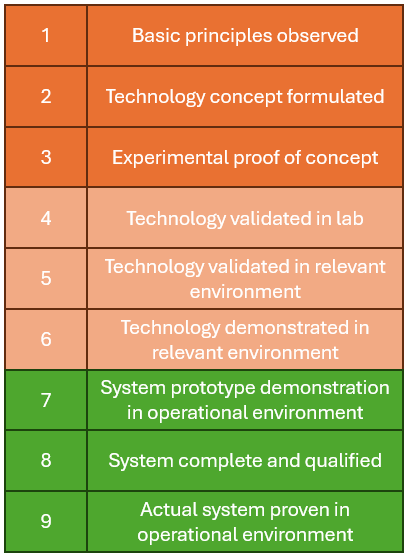

The EU’s current policy framework for research and innovation under Horizon Europe and the European Innovation Council (EIC) is held back by several limitations when compared to the US system. A major shortcoming is the insufficient funding for disruptive research. Nearly two-thirds (700 million euros) of the EIC’s annual budget support projects at technology readiness level (TRL) 5 and above, leaving early-stage research (below TRL 4) severely underfunded.[6]

Figure 1 | Technology readiness levels

Although early-stage projects are inherently high-risk and less profitable in the short run, experience from leading innovation ecosystems indicates that robust investment at these stages can catalyse breakthroughs with exponential returns. Reallocating quotas to lower TRL projects is a strategic shift aimed at bridging a critical gap in Europe’s innovation pipeline. EIC Pathfinder, the EU’s primary instrument for early-stage disruptive technologies, received only 256 million euros for 2024, compared with 4.1 billion US dollars for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in the US, clearly highlighting the existing gap.[7]

The EU’s current funding paradigms privilege more mature sectors (such as the automotive industry) that have historically justified this type of support through market stability. However, this focus somehow penalises emerging fields that instead, with adequate support, could offer far greater long-term economic returns. Europe’s static industrial structure compounds this bias – evidenced by the fact that no EU company with a market capitalisation exceeding 100 billion euros has been created from scratch in the last fifty years, in contrast to the US, where all six companies valued above 1 trillion euros emerged in the last five decades.[8]

Additionally, the chronic shortage of venture capital is dramatic. In 2023, only 5 per cent of all capital raised by venture-capital funds worldwide was raised by EU-based funds, compared with 52 per cent in the United States and 40 per cent in China.[9] The European industries working on artificial intelligence and quantum computing attract only a fraction of the worldwide related investment, which underscores systemic constraints on scaling breakthrough innovations. Although European universities produce a robust volume of patents, only about one-third are commercially exploited[10] – a clear indication of deficiencies in technology transfer. Moreover, high-tech industries in Europe achieve profit margins only about three percentage points higher than those in mid-tech industries, compared to a gap of approximately seven percentage points in the US.[11] These factors combined result in a diminished appeal for investors.

Furthermore, the depth of this gap is uneven within the EU (Figure 2). Peripheral regions face severe budgetary and infrastructural constraints that hinder their ability to cultivate and support innovative projects. In many low-innovation areas, high-potential ideas are overlooked simply because the local environment lacks the early-stage resources necessary to drive projects from TRL 1 to 5.[12] Under the current EIC funding framework, projects originating from regions with abundant capital and robust infrastructure are more likely to secure support, while those from underdeveloped regions remain neglected, which amplifies existing disparities.

Figure 2 | Innovation levels across the EU

Note: each country is assigned to a performance group based on its innovation performance relative to the EU average in 2024: leader (>125%), strong (125-100%), moderate (100-70%), emerging (<70%).

Source: Hugo Hollanders and Nordine Es-Sadki, Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2023, Luxembourg, Publications Office of the EU, 2023, p. 4, https://doi.org/10.2777/70412.

Funding Innovation Labs: Supporting Hubs for Academic-Powered Enterprises (SHAPE)

To address these systemic challenges, we propose here a new plan for Supporting Hubs for Academic-Powered Enterprises (SHAPE), based on a two-pronged approach. First, targeted funding should be provided to empower existing university-led technology hubs. This funding can enable universities to enhance their start-up support systems and better identify high-potential projects at TRL levels below 4. Factoring in the risk of over-relying on academic authority – which may lead to internal inertia or conflicts of interest – this funding should ideally be accompanied by strong recommendations for establishing independent advisory boards including external industry experts and seasoned venture capitalists.

Second, to ensure that innovation reaches underfunded regions, the fund-of-funds mechanism should be reformed in order to account for regional development. The mere reallocation of funds to these areas is insufficient on its own. It must be combined with granular capacity-building initiatives, such as partnerships with local development agencies for infrastructural improvements and tailored training programmes. This integrated strategy can contribute to addressing deep-rooted disparities in the EU.

In both directions, universities still represent the best subjects able to identify the early-stage projects with the highest potential, through enhanced access to information based on proximity. They already have the needed human capital to both identify the most promising proposals and understand the funding mechanisms.

Through targeting mechanisms, SHAPE could also address second-level issues. The design of the allocation procedures should take into consideration the sustainability of the projects from an environmental and social perspective. Furthermore, ensuring the allocation of a significant quota to marginalised groups and women-led projects is a way to foster innovative potential that could be biasedly discarded otherwise.

The initiative could be embedded within existing EU frameworks, such as Horizon Europe and its successor FP10, InvestEU and the EIC, to create a coherent and coordinated funding ecosystem. Notably, while the EU’s expenditure-to-GDP ratio on research and innovation is similar to the US’s one, only one-tenth of it is managed at the EU level, reflecting a fragmented approach to public research and innovation (R&I) funding. To revolutionise the innovation ecosystem, the consensus is that the next Framework Programme for R&I must be scaled up dramatically, with the Draghi report recommending doubling its budget to 200 billion euros for seven years. This increase should be sustained by detailed cost-benefit analyses and clear performance metrics (for example, tracking patent activity, measuring private sector engagement) to rigorously evaluate the initiative’s long-term impact.[13] A data-driven approach and robust evaluation standards should be adopted to ensure that the funding mechanism not only meets broader economic objectives but also delivers tangible, quantifiable returns. This would in turn contribute to gaining support for the expansion of the EU’s research and innovation funding within the public opinion.

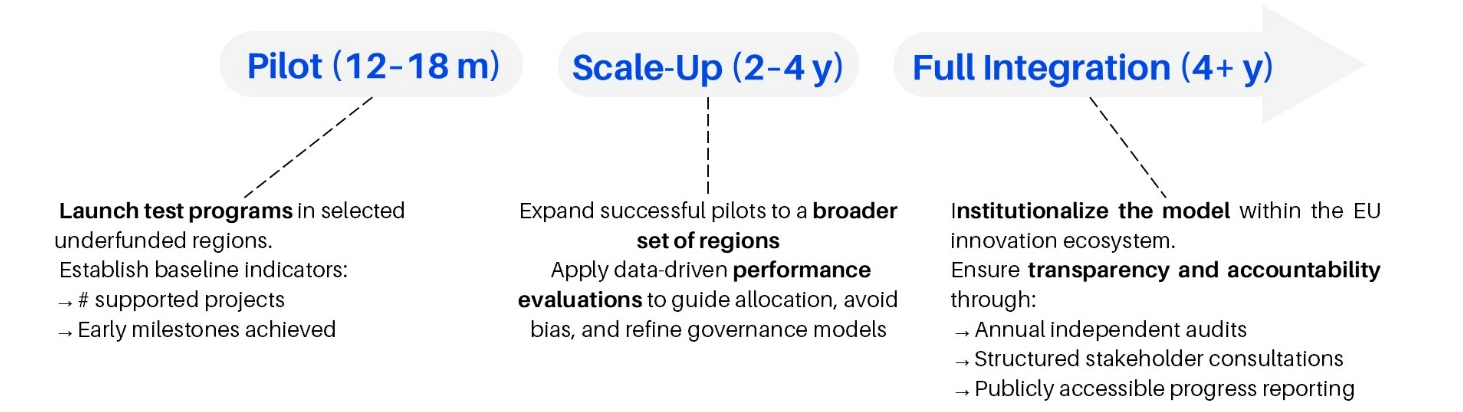

A clear implementation roadmap is also essential for translating this vision into tangible outcomes. Our plan develops over three phases (Figure 3). In the initial one (about 12 to 18 months), targeted pilot projects are launched in select underfunded regions. Baseline metrics, such as the number of early-stage projects supported and initial commercialisation milestones achieved, are established. In the second step (roughly two to four years), the most successful pilot models are scaled up to additional regions, with systematic and granular performance evaluation guiding their expansion. Finally, in the long-term phase (beyond four years), these models will be fully integrated into the broader EU innovation ecosystem. Continuous improvements will be achieved through annual independent audits, transparent stakeholder reviews and publicly available progress reports. This system makes it possible to tackle shortcomings in the original structure. Such a phased approach provides a robust and measurable pathway to accelerate the conversion of academic breakthroughs into market-ready innovations.

Figure 3 | Project roadmap with the three main phases

Looking ahead

Europe’s path to competitiveness is currently undermined by a persistent gap between academic breakthroughs and market-ready innovations. If left unaddressed, this disconnect will widen, eroding Europe’s global competitiveness, stifling job creation and exacerbating regional disparities within the EU itself. Amid the current geopolitical tensions, enhancing competitiveness by fostering stronger connections between academia and market is vital to secure the EU’s interests. Driving technological innovation internally would be an effective means of protecting the EU’s economic interests in terms of technological sovereignty. SHAPE, based on a targeted funding system to empower university-led technology hubs coupled with a reformed EU fund-of-funds mechanism, is designed to foster early-stage research and enhance dynamic collaboration between researchers, start-ups and investors. In doing so, Europe will accelerate the commercialisation of groundbreaking ideas and secure a sustainable, inclusive and technology-driven future. This is a necessary step for the Union to achieve a truly competitive global standing.

Leonardo Gallo is a Master’s Student in International Management at Bocconi University. Sakurako Maki is a Master’s Student at Sciences Po Paris. Italo Parrilli is a Master’s Student in Economic and Social Sciences at Bocconi University.

This commentary is an updated version of the winning brief from the futurEU Competition 2025, hosted by the futurEU Initiative at the Hertie School and supported by the CIVICA Alliance.

[1] Mario Draghi, The Future of European Competitiveness. Part A, September 2024, p. 33, https://commission.europa.eu/node/32880_en.

[2] European Commission, European Innovation Scoreboard 2024, Luxembourg, Publications Office of the EU, 2024, p. 7, https://doi.org/10.2777/779689.

[3] European Commission, The New European Innovation Agenda (COM/2022/332), 5 July 2022, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex:52022DC0332.

[4] European Commission, A Competitiveness Compass for the EU (COM/2025/30), 29 January 2025, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex:52025DC0030; European Innovation Council (EIC), Policy Orientations 2024, Luxembourg, Publications Office of the EU, 2025, https://doi.org/10.2777/8887334.

[5] Mario Draghi, The Future of European Competitiveness. Part A, cit., p. 23-38.

[6] Clemens Fuest et al., “Reforming Innovation Policy to Help the EU Escape the Middle-Technology Trap”, in VoxEU, 19 April 2024, https://cepr.org/node/433010.

[7] Mario Draghi, The Future of European Competitiveness. Part A, cit., p. 29.

[8] Ibid., p. 24.

[9] Chiara Fratto et al., “The Scale-up Gap. Financial Market Constraints Holding Back Innovative Firms in the European Union”, in EIB Thematic Studies, June 2024, p. 22, https://doi.org/10.2867/382579.

[10] European Commission, A Competitiveness Compass for the EU, cit., p. 4.

[11] Clemens Fuest et al., “Reforming Innovation Policy to Help the EU Escape the Middle-Technology Trap”, cit.

[12] European Commission, Science, Research and Innovation Performance of the EU 2024, Luxembourg, Publications Office of the EU, 2024, https://doi.org/10.2777/965670.

[13] Mario Draghi, The Future of European Competitiveness. Part A, cit., p. 33.