Titolo completo

AI 4 Italy: An Energy Policy Roadmap

|

A rising competition among countries and companies has emerged aimed at achieving dominance in key technologies, especially artificial intelligence (AI), triggering a race for investments. To translate such ambition into reality, several key ingredients are indispensable, starting from data centres (DCs)[1] and abundant, stable and affordable energy supply. As governments are eager to attract DCs investments, they have also become more aware of the profound AI-energy nexus.[2] Therefore, it is crucial for any country seeking to play a role in this quest to design an adequate energy policy framework that addresses the energy trilemma (security, affordability and sustainability). In this sense, Italy should develop a clear and robust energy policy roadmap for the development of AI to reduce obstacles and leverage its competitive advantages.

The AI-energy nexus: A global perspective and policy choices

Today, DCs consume 415 terawatt hours (TWh), equal to 1.5 per cent of the world’s electricity consumption. Today, 85 per cent of global electricity consumption is concentrated in the US, Europe and China. However, it amounts to more than 4 per cent of electricity consumption in the US, less than 2 per cent in Europe and 1.1 per cent in China.

Given mainly the AI ambitious plans across the world,[3] global DCs electricity consumption is expected to more than double (945 TWh) by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency’s estimates.[4] Ensuring security and affordability of energy supply is of paramount importance, forcing governments and companies to assess the contribution of each energy source. Globally, renewables are expected to meet half of such additional demand, followed by natural gas and coal. In this expansion, innovation will be crucial, also in supporting sustainable solutions. For example, investing in energy storage would allow to buffer renewables’ intermittency and grid expansion, while ensuring sustainable energy supplies. The environmental footprint of AI is particularly a concern for tech companies’ climate targets; thus, a new wave of investment and deals in clean and low-carbon energy sources, including geothermal and nuclear, have been announced.

Several energy strategies for AI among states are emerging due to different public policies and energy resource availability. For example, the US has relied on natural gas for 40 per cent of electricity for DCs. Despite some bottlenecks faced by the gas industry,[5] gas’ relevance may further increase as it may be the fuel for expected DCs demand growth (up to 12 per cent of the US electricity need by 2028).[6] By contrast, China largely relies on coal (70 per cent of electricity for DCs).

An energy bipolarity is emerging, including on AI-energy, between these two major powers. The Trump Administration, through its “One Big, Beautiful Bill Act”, embraces mainly US fossil fuels resources combined with severe subsidy cuts to solar and wind. However, such a decision may backfire as it prevents new, much-needed supply, potentially causing a trade-off with LNG export ambition, affecting affordability for American citizens, and ultimately undermining tech companies’ climate strategies. By contrast, China is now the largest renewable market, which is expected to continue, although coal remains relevant in the Chinese power sector. To further leverage its advantage and overcome some constraints, Beijing has worked on powering clean energy to its AI ambition, including through the “East Data, West Computing” national project in 2022.[7] Moreover, different energy market structures can generate additional comparative advantages.[8]

Other players, notably the Gulf countries, have also been increasingly stepping into the AI quest through a whole-of-government approach that integrates private and public entities, aiming to leverage their vast financial and abundant energy resources as they consider AI a key pillar of their economic diversification strategies.[9]

Europe between a rock (USA) and a hard place (China)

The European Union needs to catch up if it seeks to fulfil its AI ambition.[10] Forecasts expect that DC demand will at least reach 150 TWh by 2030 (more than 170 per cent increase since 2022). The European AI goals are fundamentally challenged by multiple factors, including public capital constraints, higher real estate prices and over-regulation – something increasingly under pressure by public and private entities.[11] The political evolution will certainly shape AI developments in the EU, alongside natural, infrastructure and social factors.

From an energy perspective, two key challenges are related to higher energy prices (compared to competitors) and grid bottlenecks. These two factors entail critical social and industrial questions and they will shape AI developments – alongside political commitment. DCs across Europe have been expanding (more than 1,000 in 2024),[12] accounting for over 3 per cent of total electricity consumption in 2024.[13] As of today, power demand is highly and disproportionately concentrated in very few locations, known as FLAPD (Frankfurt, London, Amsterdam, Paris and Dublin), accounting for at least one-third of the total national DCs. Such concentration is due to multiple commercial factors, but it causes significant stress on power grids, raising questions about future capacity expansion.[14]

The Irish grid operator imposed a moratorium on new DCs until 2028 in the Dublin area due to concerns over blackouts.[15] DCs in Ireland consume 21 per cent of total electricity in 2023 and almost 80 per cent in Dublin, fostering concerns of social fairness and potentially competition among different consumer groups. Moreover, connecting DC to the national grid can take up to 13 years in Europe’s digital hubs, urging member states to revise permitting procedures.[16]

Availability of abundant renewable and low-carbon energy supply will play a critical pull effect in DCs investments to ensure cheap and sustainable energy. Simultaneously, political instability may hinder national ambitions. For example, France presented a 109 billion euro infrastructure investment plan with the goal to unleash AI development. Although the country can benefit from its nuclear energy capabilities, which ensure low-carbon energy supplies and lower prices,[17] the political turmoil and macroeconomic challenges may deter investments. In short, political, natural and physical factors are expected to further shape European AI map. Europe could see a shift in DC investments from traditional hubs to new locations mainly driven by grid issues and different national energy mixes.

Member states need to continue to decarbonise their power sector, accelerating low-carbon energy deployment. This will also address high energy prices. At the same time, they need to ensure higher investment to increase adequate power infrastructure. According to the Draghi report, the EU should allocate 0.9 euro in grid investment for every euro spent on clean power during the 2022-2040 period to achieve EU climate targets. The report assesses that grid investments alone will require around 90 billion euros each year over the 2031-2040 period, with a potential increase in energy bills for households and companies.[18]

The European Commission has been working on several initiatives regarding these two domains (energy prices and infrastructure). Concerning high energy prices, the Commission presented the Affordable Energy Action Plan, alongside its Clean Industrial Deal, in February 2025.[19] The Act envisages several measures addressing from short-term cost redistribution to structural measures to reduce supply costs. In December 2025, the Commission issued also the EU Grids Package highlighting the need for expanding, modernising and integrating EU electricity networks.[20]

What’s for Italy and what way ahead?

Among member states, Italy has increased its footprint in the digital domain – including with top supercomputers. DCs have more than tripled since 2024 – more than any other EU country, also due to a slowdown in traditional hubs (FLAPD). Italy also ranked within the top 20 countries by private investment in AI, with around 0.86 billion US dollars in 2024. In November 2025, a new strategy was issued to further sustain the momentum.[21] Furthermore, recent laws (i.e., DL Energia) address the permitting procedures, which envisage the role of the regions for the approval of DC up to 300 MW and that of the Ministry of Environment and Energy Security for larger projects.[22]

As of today, DC facilities are highly concentrated around industrial hubs, especially the area around Milan (37 per cent of national DC capacity) and consume around 3.9 TWh. AI-related driven consumption is expected to rise as additional DCs come online – especially hyperscales announced by big tech companies. According to data provided by the national transmission system operator, Terna, there were 68.4 gigawatts (GW) of DC connection requests at the end of November 2025.[23] Based on estimates, it is more likely that around 2.0 GW will come online by 2030, which would mean an additional 14 TWh per year.[24]

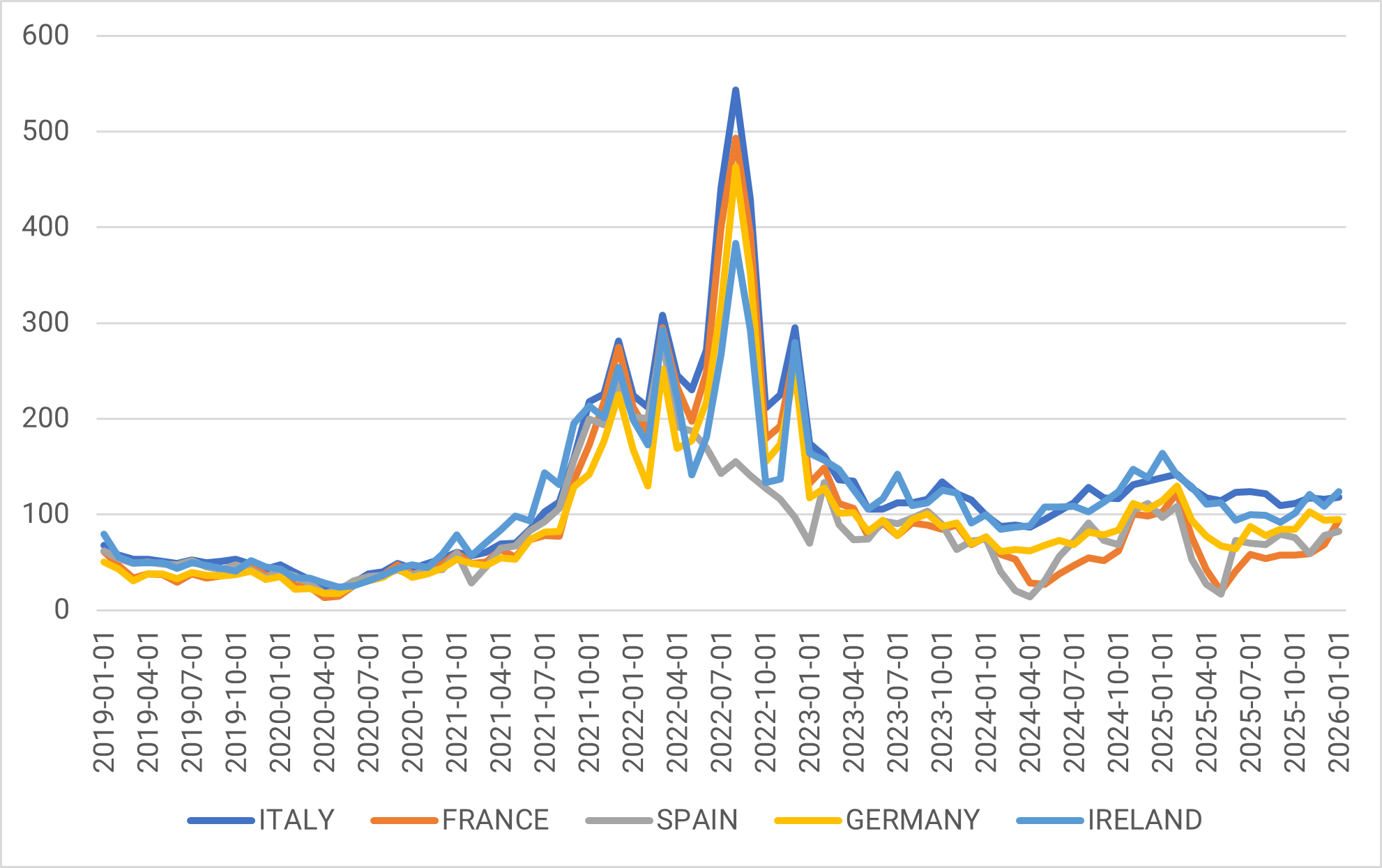

To fully satisfy this growth, Italy needs to address its generation and transmission constraints; otherwise, price spikes, social opposition and delays will be the new normal. Currently, the main disadvantage comes from higher energy prices compared to not only international players, but also European peers (Figure 1). While this disadvantage is due also to fixed costs (e.g., VAT, network costs), a major factor is related to natural gas’s relevance in the Italian power sector (around 50 per cent of power generation) and high import dependence rates (90 per cent).

Figure 1 | Wholesale electricity prices in key European member states (euro/MWhe)

Source: Author’s elaboration on Ember data.

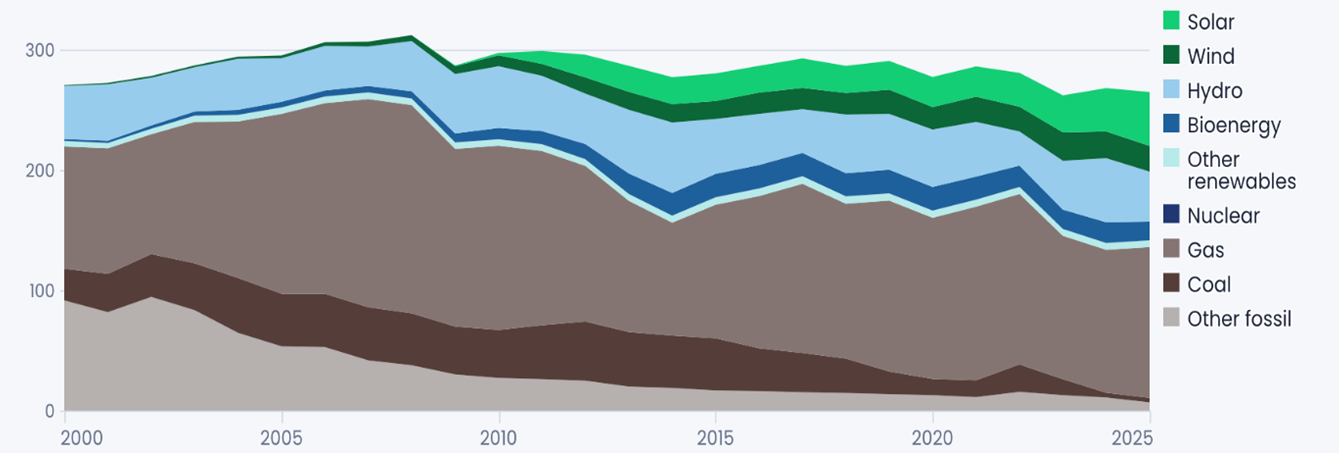

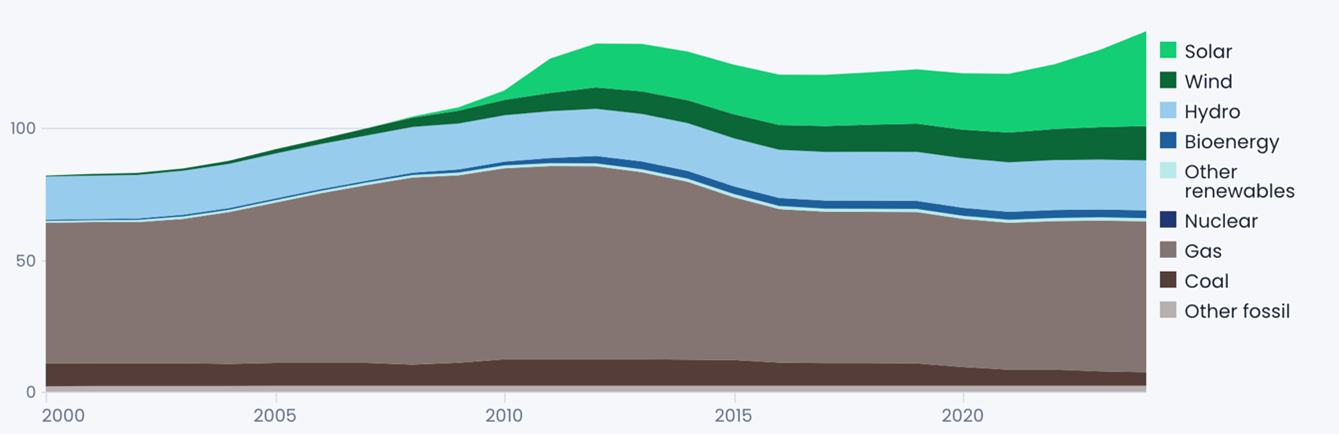

On the generation and price side, Rome should accelerate the ramp-up of renewable deployment also promoting the use of power purchase agreements to reduce price volatility. There have been positive developments as Italy has installed around 13 GW, following the removal of some bureaucratic barriers, since the start of the energy crisis in 2022. However, Italy has set a target of around 131 GW of renewable capacity by 2030 (74.5 GW at the end of 2024). To achieve it, the country will need to elevate its deployment rate substantially. Especially since the rate has slowed down in 2025 (+7.2 GW of renewable capacity) – down from 7.5 GW in 2024 and well below the 9.9 GW annual rate required to reach the 2030 target.[25] Furthermore, Italy needs to overcome its chronic barriers to keep an adequate deployment rate. A key obstacle is certainly inconsistent and conflicting policies regarding renewables and energy in general.[26] For example, Italy’s National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) does not foresee any phase-out of natural gas. Similarly, the Plan considers the contribution of nuclear (8 GW by 2050) despite economic and political challenges. This may be further embraced by policymakers to ensure baseload supply. Despite the challenges, the AI revolution (and its electricity demand) represents a positive economic signal for capital-intensive investments in energy sources and infrastructure as well as for fostering innovation.[27] Building all the required, capital-intensive generation and transmission infrastructure requires demand security. AI may ensure it after decades of stagnated electricity consumption. Indeed, today’s electricity consumption is at the same level to 2000 (around 314 TWh) after having peaked in 2008 (352 TWh).

Figure 2 | Italy’s electricity generation, 2000-2025 (TWh)

Figure 3 | Italy’s electricity capacity, 2000-2025 (GW)

Source: Ember.

To overcome both generation and transmission constraints, Italy could pursue different strategies, starting from supporting flexibility,[28] to power its AI ambition. Firstly, Italy could develop a data and computing strategy, similar to China’s “East Data, West Computing”, to sustain DC location in renewable-rich areas. Indeed, Italy has the greatest potential for renewable energy, especially solar, far from traditional hubs located in the Northern regions. Deploying DC there could position Southern Italy as a potential digital hub in the Mediterranean as highlighted in the national Strategy. Indeed, alongside renewable potential, Italy’s Southern regions are at the junction of multiple international subsea cables with great capacity, such as BlueMed, 2Africa, SeaMed and Quantum Cable. Alongside cable interconnection, Italy, through Terna, is working on expanding its power interconnections both nationally and internationally, which will ensure resilience to the system.[29] Secondly, innovation in DCs[30] may offer additional flexibility to the workloads.[31] Thirdly, a combination of flexible grid connection and bring-your-own capacity arrangements may help accelerate access to grid power, maintain reliability and improve affordability for all customers.[32] Lastly, Italy needs to sustain the positive developments on batteries, building on its 10 GWh MACSE incentive mechanism.[33]

Pier Paolo Raimondi is Senior Research Fellow in the ‘Energy, climate and resources’ programme at the Istituto Affati Internazionali (IAI).

[1] McKinsey, “What Is a Data Center?”, in McKinsey Articles, 29 July 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-a-data-center.

[2] International Energy Agency (IEA), Energy and AI, April 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai.

[3] This growth is mainly driven by AI-based workloads, which are expected to account for 70 per cent of the projected demand for data centre capacity by 2030. See: McKinsey, “What Is a Data Center?”, cit.

[4] IEA, Energy and AI, cit., p. 14.

[5] Dempsey, Harry et al., “The Fallout from the AI-fuelled Dash for Gas”, in Financial Times, 22 October 2025, https://www.ft.com/content/dfd87d3d-a386-4706-a4ba-9f9274760111.

[6] Shehabi, Arman et al., 2024 United States Data Center Energy Usage Report, Berkeley, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, December 2024, https://doi.org/10.71468/P1WC7Q.

[7] Raimondi, Pier Paolo, The AI-Energy Nexus: A Mapping of Trends and Applications for Oil and Gas Companies, Rome, IAI, September 2025, p. 20, https://www.iai.it/en/node/20592.

[8] Zijing Wu, and Eleanor Olcott, “China Offers Tech Giants Cheap Power to Boost Domestic AI Chips”, in Financial Times, 4 November 2025, https://www.ft.com/content/cad2cdd6-7cce-4de3-8710-977de667378c.

[9] Raimondi, Pier Paolo, The AI-Energy Nexus, cit., p. 9-10.

[10] European Commission DG for Communication website: Shaping Europe’s Leadership in Artificial Intelligence with the AI Continent Action Plan, https://commission.europa.eu/node/38607_en.

[11] Moens, Barbara, “EU Set to Water Down Landmark AI Act after Big Tech Pressure”, in Financial Times, 7 November 2025, https://www.ft.com/content/af6c6dbe-ce63-47cc-8923-8bce4007f6e1.

[12] EU27+UK.

[13] Eurolectric, Power Barometer 2025. In Shape for the Future, September 2025, https://powerbarometer.eurelectric.org.

[14] Meyer, Robinson, “Amid Rising Local Pushback, U.S. Data Center Cancellations Surged in 2025”, in Heatmap News, 12 January 2026, https://heatmap.news/?p=2674856532.

[15] O’Brien, Matt, “Ireland Embraced Data Centers that the AI Boom Needs. Now They’re Consuming Too Much of Its Energy”, in AP News, 19 December 2024, https://apnews.com/article/6c0d63cbda3df740cd9bf2829ad62058.

[16] Cremona, Elisabeth and Pawel Czyzak, “Grids for Data Centres: Ambitious Grid Planning Can Win Europe’s AI Race”, in Ember Insights, 18 January 2025, https://ember-energy.org/?p=12538.

[17] McGeady, Cy and Rebecca Riess, “Great Power Competition: Surveying Global Electricity Strategies for AI”, in CSIS Analysis, 8 May 2025, https://www.csis.org/node/116210.

[18] Draghi, Mario, The Future of European Competitiveness. Part B, In-depth Analysis and Recommendations, September 2024, p. 22, https://commission.europa.eu/node/32880_en.

[19] European Commission, Action Plan for Affordable Energy (COM/2025/79), 26 February 2025, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex:52025DC0079.

[20] European Commission, European Grids Package (COM/2025/1005), 10 December 2025, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex:52025DC1005.

[21] Italian Ministry of Enterprises and Made in Italy, Una strategia per l’attrazione in Italia degli investimenti industriali esteri in Data Center, November 2025, https://www.mimit.gov.it/it/strategie/datacenter.

[22] Law-decree No. 175 of 21 November 2025: Misure urgenti in materia di Piano Transizione 5.0 e di produzione di energia da fonti rinnovabili, https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legge:2025-11-21;175.

[23] Terna Database: Econnextion (access on 22 January 2026), https://dati.terna.it/en/econnextion#consumer-users.

[24] Moroni, Mauro, “I data center in Italia: da 50 GW di rumore a 5 GW di realtà”, in QualEnergia, 2 September 2025, https://www.qualenergia.it/?p=589923.

[25] Tavazzi, Lorenzo et al., “Il mercato delle rinnovabili: il consuntivo per il 2025 e le prospettive per il 2026”, in RiEnergia, 7 January 2026, https://rienergia.staffettaonline.com/articolo/35873/Il+mercato+delle+rinnovabili:+il+consuntivo+per+il+2025+e+le+prospettive+per+il+2026/Lorenzo+Tavazzi+e+Marco+Schiavottiello+.

[26] Raimondi, Pier Paolo, “Le politiche energetiche e climatiche”, in Ferdinando Nelli Feroci and Leo Goretti (eds), L’Italia nell’anno delle grandi elezioni. Rapporto sulla politica estera italiana. Edizione 2024, Rome, IAI, January 2025, p. 50-56, https://www.iai.it/en/node/19396.

[27] Bortoni, Guido and Federico Gallo, “Data center, attirarli conviene al Sistema elettrico italiano”, in EnergiaOltre, 5 August 2025.

[28] Brown, Tom et al., “How Data Centres Can Chase Renewable Energy across Europe”, in Bruegel First Glance, 20 February 2025, https://www.bruegel.org/node/10677.

[29] Terna, 2024-2028 Industrial Plan Update. Empowering Tomorrow (slides), 25 March 2025, https://www.terna.it/en/media/news-events/detail/2024-2028-industrial-plan-update.

[30] Energy Innovation, Data Center Demand Flexibility, 11 March 2025, https://energyinnovation.org/report/data-center-demand-flexibility.

[31] Spieler, Marc, “How AI Factories Can Help Relieve Grid Stress”, in NVIDIA Blog, 1 July 2025, https://blogs.nvidia.com/?p=82909.

[32] Brancucci, Carlo et al., Flexible Data Centers: A Faster, More Affordable Path to Power, Camus, encoord and Princeton ZERO Lab, December 2025, https://www.camus.energy/flexible-data-center-report.

[33] Petrovich, Beatrice, European Electricity Review 2026, Ember, 22 January 2026, https://ember-energy.org/latest-insights/european-electricity-review-2026/early-signs-of-the-impact-of-batteries/#early-signs-of-batteries-starting-to-meet-demand-i.