Titolo completo

The European Defence Industry Programme: The Last Piece of the EU Defence Puzzle?

|

On 8 December 2025, the Council of the European Union adopted the European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP) regulation,[1] which represents the last piece of the puzzle of the EU toolbox for defence industrial policy – and may be the most effective one for the sake of European cooperation and integration in this field.

A regulation for a small but growing budget

The EDIP regulation has been negotiated on the basis of the proposal put forward by the first von der Leyen Commission in March 2024. This instrument, the most recent part of a wider array of EU tools introduced in support of the European Defence Technological Industrial Base (EDTIB), provides for the allocation of 1.5 billion euro grants for the period 2026-2027, of which 300 million will constitute the Ukraine Support Instrument. Over the short term, it is a very limited funding; however, it represents the blueprint for a much larger endowment in the 2028-2034 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), as the Commission proposed 131 billion euros for defence and space for that timeframe.[2] The EDIP builds on instruments already adopted with a view to supporting common procurement, in particular the European Defence Industry Reinforcement through common Procurement Act (EDIRPA), and to strengthening production capacities, such as the Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP), with the aim of rationalising them through greater structuring and longer timelines.

The Commission’s way to become a defence actor

As such, EDIP regulations show a recurring Commission’s pattern in this policy field: it begins with a new regulation entailing a limited budget to set up and test the legal and institutional framework, and then it refines and empowers the tool with a larger financial envelope. It happened already in the 2010s with the 90-million-euro Preparatory Action Defence Research (PADR), followed by the 7,3-billion-euro European Defence Fund (EDF). Such an incremental approach also enables the Commission to manage and overcome disagreements and oppositions, while building in-house human resources capacities through the Directorate-General for Defence Industry and Space (DG DEFIS). One decade after the 2016 decision to launch the PADR, the Commission is nowadays a powerful and recognised actor in the defence domain, featuring even a Commissioner for Defence and Space, whose power is set to further grow via EDIP and the next MFF. Therefore, from an Italian perspective, it is important to actively participate from the outset through to the negotiation and final implementation of each tool, such as EDIP, given both their importance in themselves and their future evolution within the EU defence industrial toolbox.

The potential of EDIP flagship projects

As for EDIP, three priorities will guide its implementation: competitiveness of the European defence industry, the timely availability of products, and the efficiency and resilience of the supply chain.[3] They are, in turn, reflected in four funding streams.[4] The first concerns common procurement initiatives, which must be undertaken by at least three countries, of which at least two member states. The second focuses on strengthening the production capacities of critical products, with the aim of making the defence industry able to quickly respond to the demand of such products. The third involves the launch of European Defence Projects of Common Interest, also known as flagship projects, namely collaborative development projects for critical military capabilities. The European Commission has so far identified four projects of such kind, namely the European Drone Defence Initiative, the Eastern Flank Watch, the European Air Shield, and the European Space Shield.[5] Finally, the EDIP will finance support activities aimed at fostering interchangeability and interoperability, as well as activities designed to facilitate the entry of SMEs, mid-caps and start-ups into the defence market.

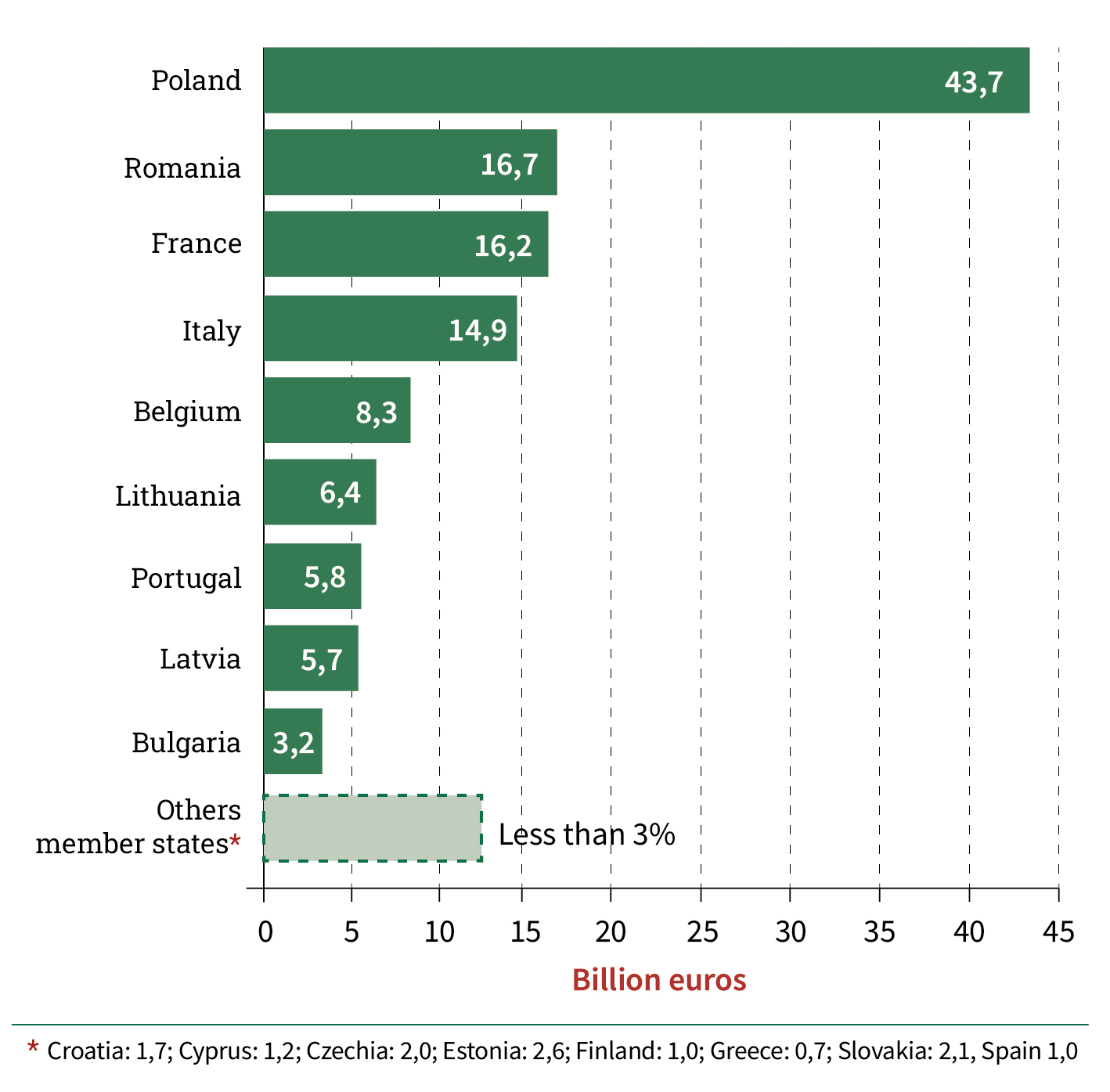

The flagship projects are particularly important, considering another EU tool for defence industrial policy: the Security Action for Europe (SAFE) programme, which will lend 150 billion euros to member states to be invested in defence equipment by 2030. The tentative allocation sees around 43,7 billion for Poland, 16,7 for Romania, 16,2 for France, 14,9 for Italy, 8,3 for Belgium, 6,4 for Lithuania, 5,8 for Portugal, 5,7 for Latvia, 3,2 for Bulgaria,[6] and less than 3 billion euros for another handful of member states (Figure 1). National governments have presented their industrial plans to spend the requested loans in November 2025, and they are being validated by the Commission. Considering the tight timeline to both apply for loans and spend them, it is likely that much of the fund allocated will go to existing procurement projects, whether national, bilateral or mini-lateral, as well as to commercial-off-the-shelf acquisitions. Actually, SAFE regulations are meant to satisfy urgent requirements to fill priority gaps through the procurement of state-of-the-art capabilities, not to launch pan-European cooperative procurement. The latter should, rather, be the exact goal of EDIP flagship projects. Indeed, planning in 2026 those projects to be implemented in the 2028-2034 timeframe makes it possible to achieve the political, military and industrial convergence necessary for ambitious procurement of next-generation capabilities which single member states are not able to develop and procure on a national or bilateral basis.

Figure 1 | SAFE programme tentative allocations

The case of integrated air and missile defence

A perfect example in this regard would be an ensemble of capabilities for the Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD) of Europe against a broad array of threats, ranging from drones to hypersonic missiles. Regardless of buzzwords such as “Drone Wall” and alike, Europe’s IAMD is already organised and well-functioning in operational terms within the NATO framework, as proven by the shot-down of drones entering the Polish airspace from Belarus in September 2025.[7] The EU should not reinvent the wheel, but rather co-fund the cooperative development and procurement of sensors, effectors and command & control systems by European companies for European armed forces, to be federated according to NATO standards within the allied IAMD. That would be the most effective way to allocate the bulk of EDIP funding for a flagship project serving both the operational needs of Europe’s defence and European strategic autonomy in technological and industrial terms.

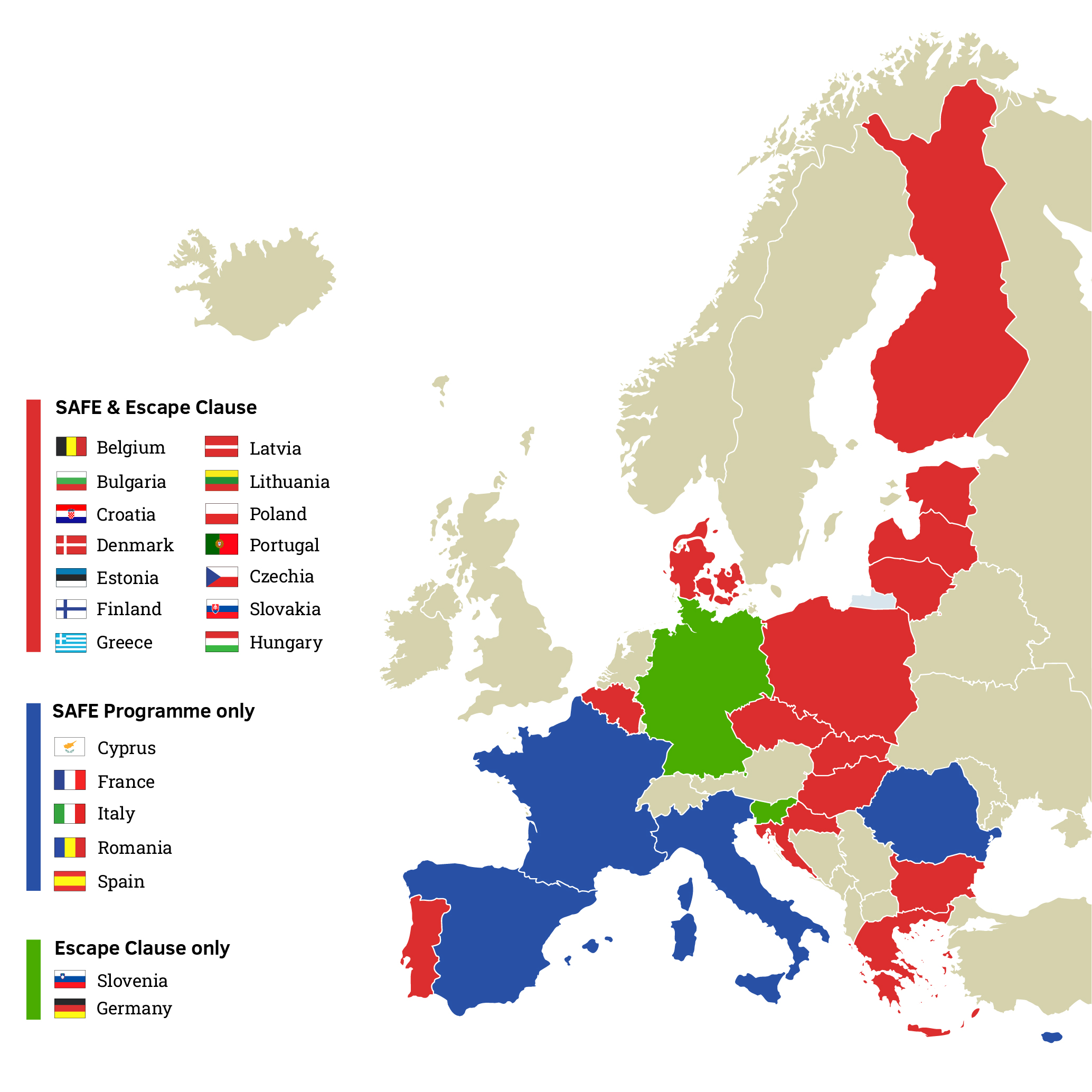

From Italy’s point of view, EDIP is complementary to SAFE insofar as it encourages European defence cooperation in the mid-long term, and there is a dire necessity to upgrade and expand Italian IAMD capabilities. Moreover, through MBDA, Leonardo and their supply chain, the Italian defence industrial base is able to both contribute to an EDIP flagship project and benefit from its investments. The position of Germany is crucial in this regard, for two reasons. First, Berlin increased its defence budget by 30 per cent from 2024 to 2025, and it will reach 83 billion euros in 2026. Second, the German government launched already in 2022 the European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI) for the joint procurement of IAMD capabilities (Figure 2) – however most of such capabilities are from the US and Israel, with a negative impact on the perspective of autonomously developing the technologies that enable them. The rearmament of Germany, mostly on a national basis, is set to change in the mid-long term the military and industrial balance within the EU,[8] and both Brussels institutions and other member states have to take it into account to find win-win solutions, starting from the IAMD case. This is particularly important from an Italian perspective, considering the growing industrial cooperation with German companies in the land, missile and space sectors.

Figure 2 | Member states of the European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI)

The EDIP transatlantic balancing act

To ensure that EDIP is genuinely geared towards strengthening European production capacities, a clause has been introduced stipulating that the cost of components originating outside the EU and partner countries, and, with regard to the Ukraine Support Instrument, Ukraine, must not exceed 35 per cent of total costs.[9] Moreover, no component may originate from non-partner countries that are in conflict with the European Union’s defence and security interests: a rather nuanced clause that places important political choices on participating member states and EU institutions when it comes to the selection of trusted non-EU suppliers, i.e. from the US. That percentage has been a thorny issue, causing much of the delay in approving the regulation.

Italy has strongly advocated for the 65-35 per cent balance, in order to safeguard important supply chains involving the UK, Norway, Canada and the US. The interdependence with the US is both a technical and political issue, considering the tensions brought by the Trump administration in the transatlantic relations and the EU’s quest for a higher degree of strategic autonomy. Considering the EDTIB’s multiple dependencies on American supplies, the 65-35 per cent balance allows a robust growth of intra-UE industrial capacities without creating the huge increase of costs and timelines for the military customers – and thus the EU taxpayers – that would be caused by a total closure of existing extra-EU supply chains. Moreover, such a balance did fit well with the Italian – and largely European – balancing act to avoid a trade war with NATO’s most important ally.

A two-way street with the Ukrainian industry

As previously mentioned, a significant share of the EDIP funds, amounting to 20 per cent of the total, will be allocated to the Ukraine Support Instrument, whose objective is to support and modernise the Ukrainian defence industry and to promote its greater integration into the European defence industrial ecosystem.[10] Although modest in absolute terms, this sum represents a significant share of the allocation envisaged for the EDIP. This choice demonstrates, on the one hand, that military support to Ukraine through the backing of its defence industry remains, at present, a priority for Europe. On the other hand, it highlights how that same Ukrainian industry represents an opportunity for the EDTIB to integrate, as far as possible, innovation, technologies, processes and expertise developed within an industrial sector directly involved in the conflict with Russia.

Finally, a novel element introduced by the EDIP Regulation is the establishment of an EU-level security of supply regime aimed at ensuring the availability of defence products even in the event of shocks, thereby increasing the resilience of the system. Such a regime had previously been discussed in several formats, including within the European Defence Agency, and linking it to EDIP funding may increase the possibilities of making it real. This approach will, in theory, take the form of a set of measures designed to ensure that defence products, as well as the related components, raw materials and critical services required for their production, remain available even in times of crisis.[11]

A puzzle or a patchwork? Prioritisation as mitigation

In conclusion, the combination of EDIP and SAFE truly represents a quantum leap in terms of European investments in defence: a total of 281 billion euros has been tabled from 2026 to 2034, providing the kind of long-term visibility which enabled defence industries in Europe to make their own investments in production capacities. In addition, the activation of the Stability Pact escape clause for defence investments, up to 1,5 per cent of GDP with respect to the 2021 threshold, allowed by the second von der Leyen Commission and activated by 16 member states including Germany (Figure 3),[12] enables more national investments in this sector.

Figure 3 | Activation of the Stability Pact escape clause and request of SAFE loans

However, despite the flourishing of strategic documents in 2024-2025[13] – not to mention pre-existing initiatives like Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), Coordinated Annual Review of Defence (CARD) or EDF – the EU toolbox for defence industrial policy still looks more like a patchwork of stand-alone elements than a coherent puzzle. Such a fragmented reality is here to stay, and no quick-fix solution is available. Against this backdrop, each member state will continue to make its own procurement choices within the perimeter of targets set by the NATO Defence Planning Process, according to military, industrial and political evaluations on a national basis.

The only mitigation of such persistent European fragmentation may come from flagship projects, depending on their implementation in 2028-2034. If EDIP will distribute and dilute its financial firepower on a number of small projects, by following the EDF negative example, it will not benefit in a meaningful way Europe’s military capabilities, nor its industrial capacities. In contrast, if it prioritises most of the budget on IAMD and a maximum of another couple of pan-European priorities, it will make the difference by becoming the most effective element of the EU puzzle – or patchwork – for the sake of European cooperation and integration.

Nicolò Murgia is a Junior Researcher in the “Defence, security and space” programme at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI). Alessandro Marrone is Head of IAI’s “Defence, security and space” programme.

[1] Council of the EU, European Defence Industry Programme: Council Gives Final Approval, 8 December 2025, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2025/12/08/european-defence-industry-programme-council-gives-final-approval.

[2] European Commission website: The 2028-2034 EU Budget for a Stronger Europe, https://commission.europa.eu/node/42716_en.

[3] Council of the EU, European Defence Industry Programme, cit.

[4] European Parliament and Council of the EU, Regulation (EU) 2025/2643 of 16 December 2025 Establishing the European Defence Industry Programme and a Framework of Measures to Ensure the Timely Availability and Supply of Defence Products (‘EDIP Regulation’), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2025/2643/oj/eng.

[5] Blockmans, Steven and Daniel Fiott, “European Defence Projects of Common Interest: From Concept to Practice”, in European Parliament Studies, January 2026, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EXAS_STU(2026)775284.

[6] European Commission DG for Defence Industry and Space website: SAFE | Security Action for Europe, https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/node/832_en.

[7] Marrone, Alessandro, “Estonia: i Mig russi, gli F-35 italiani ed una NATO più europea”, in AffarInternazionali, 20 September 2025, https://www.affarinternazionali.it/?p=114147.

[8] Nones, Michele, “Quo vadis Germania?”, in AffarInternazionali, 23 December 2025, https://www.affarinternazionali.it/?p=115569.

[9] Council of the EU, “European Defence Industry Programme”, in Explainers, updated 8 December 2025, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/defence-industry-programme/#ramp-up.

[10] Ibid.

[11] European Parliament and Council of the EU, Regulation (EU) 2025/2643 of 16 December 2025, cit.

[12] Council of the EU, “National Escape Clause for Defence Expenditure”, in Explainers, updated 10 October 2025, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/national-escape-clause-for-defence-expenditure-nec/#which.

[13] European Commission, A New European Defence Industrial Strategy: Achieving EU Readiness through a Responsive and Resilient European Defence Industry (JOIN/2024/10), 5 March 2024, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celeX:52024JC0010; European Commission, Joint White Paper for European Defence Readiness 2030 (JOIN/2025/120), 19 March 2025, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex:52025JC0120; European Commission, Preserving Peace - Defence Readiness Roadmap 2030 (JOIN/2025/27), 16 October 2025, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex:52025JC0027.