Titolo completo

Italy’s Foreign Policy in a World in Flux

|

In 2025, Italy had to reckon with an increasingly unstable and complex international scenario. Donald Trump’s return to the White House was followed by a number of initiatives that called into question the very fabric of the liberal International order, including the legitimacy of established multilateral fora, the architecture of International trade and the transatlantic relationship, both at the NATO and EU levels. While the Russian war against Ukraine entered its fourth year, the US repeatedly seemed to falter on its support for Kyiv’s cause and its commitment to European security at large. The Gaza war also continued to cause thousands of casualties until a fragile truce was reached in the autumn. In the meantime, the Middle East was on the verge of being embroiled in another major conflict as the US and Israel launched a 12-day-long military attack on Iran in June.

Rome caught between Washington and Brussels

Against this tense backdrop, Rome’s relationship with the European Union evolved amidst heightened pressure on European cohesion. The strain on transatlantic relations caused by Trump’s confrontational approach towards European allies accentuated the challenge of reconciling Italy’s European commitments with Rome’s ambition to pursue a privileged political channel with Washington. Overall, Italy’s foreign policy towards the EU was characterised by a pragmatic activism aimed at influencing European decision-making while avoiding open confrontation or structural misalignment with Washington.

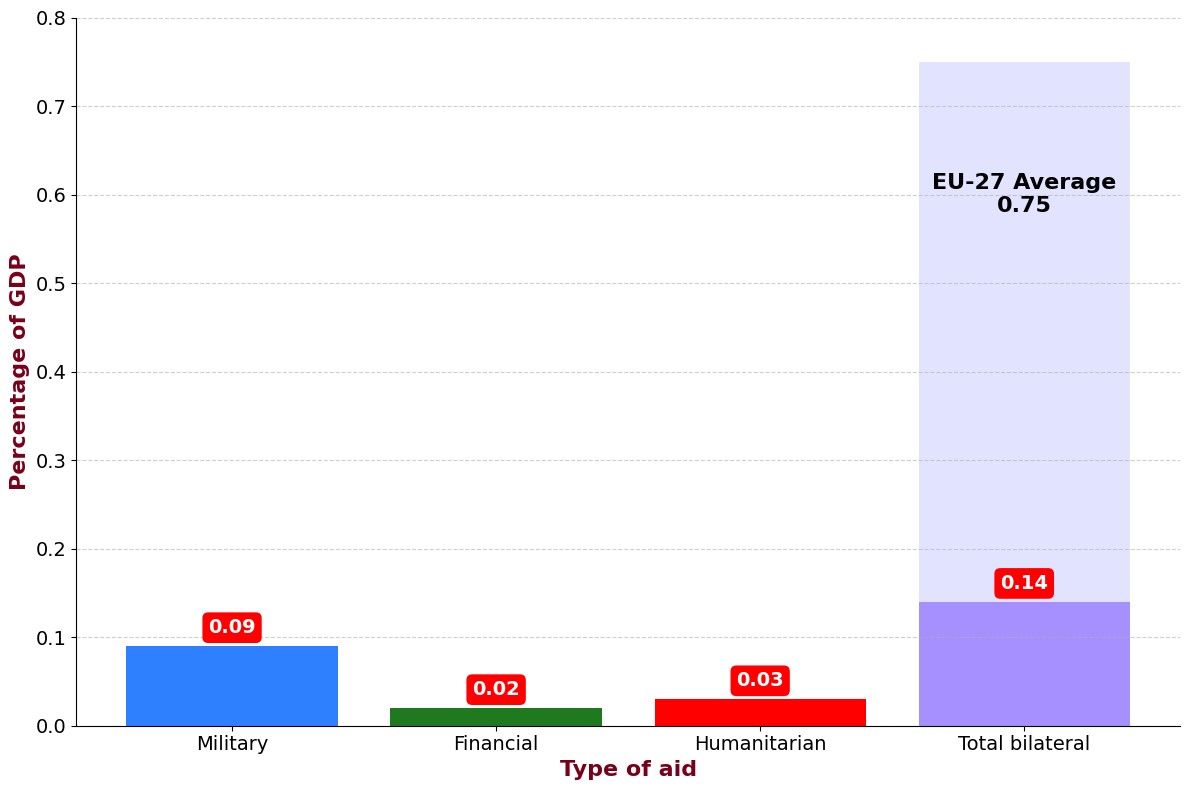

Regarding the Russian war against Ukraine, Italy remained firmly embedded in the European consensus. Rome supported all EU sanctions packages against Russia and endorsed continued political, military and financial assistance to Kyiv. The hosting of the Ukraine Recovery Conference in July 2025[1] underlined Italy’s willingness to contribute to Kyiv’s long-term stabilisation and reconstruction. At the same time, Rome adopted a cautious operational posture, distancing itself from initiatives involving direct military guarantees or envisioning troop deployments on Ukrainian territory outside a UN framework; furthermore, the overall bilateral aid provided by Italy to Ukraine remained comparatively modest (0.14 per cent of the GDP between January 2022 and October 2025, as against a EU-27 average of 0.75). This approach reflected internal divisions between governing parties as well as a strategic preference for preserving unity, as much as possible, within the Euro-Atlantic architecture.

Figure 1 | Italian contribution to Ukraine by type of aid (% of GDP, January 2022-October 2025)

Source: Kiel Institute, Ukraine Support Tracker, updated on 10 December 2025, https://www.kielinstitut.de/topics/war-against-ukraine/ukraine-support-tracker.

Italy’s EU engagement was marked by a selective but constructive approach to European strategic autonomy. Rome supported the strengthening of the EU’s defence dimension, particularly in terms of industrial cooperation and capability development. To support this, Rome made use of EU-level instruments such as the Security Action for Europe (SAFE) programme, applying for 14.9 billion euros in loans. Finally, Italy actively contributed to the development of the bloc’s first defence industry programme (EDIP).[2]

Migration policy remained a central and sensitive area of Italy-EU interaction, focused on implementing previously agreed measures rather than launching new initiatives. Rome worked closely with the European Commission on the rollout of the Pact on Migration and Asylum, emphasising the need for more effective return mechanisms and stronger partnerships with countries of origin and transit. The bilateral agreement with Albania on migrant centres, despite major judicial obstacles, was defended by the Italian government as consistent with emerging EU norms and a potential test case for future European solutions. More broadly, Italy sought to frame migration management as a shared European responsibility, advocating solidarity mechanisms and coordinated action.

Transatlantic relations vis-a-vis the second Trump presidency

Transatlantic relations inevitably represented a defining pillar of Italy’s foreign policy in 2025. The return of Donald Trump to the US presidency introduced new volatility into US-EU relations, particularly regarding trade policy, security burden-sharing and support for Ukraine. In this context, Italy distinguished itself by maintaining a continuous dialogue with Washington, while seeking to avoid a rupture with its European partners.

Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni leveraged ideological proximity to the US radical-right leadership and strong personal ties with President Trump to secure privileged access to the White House. This access translated into frequent bilateral meetings and contacts. Italian diplomacy refrained from public criticism of the US administration, while trying to prevent trade retaliation – especially through tariffs – and to limit the risk of a transatlantic breakdown over European security and Ukraine. The actual results of this difficult balancing attempt, however, were uncertain.

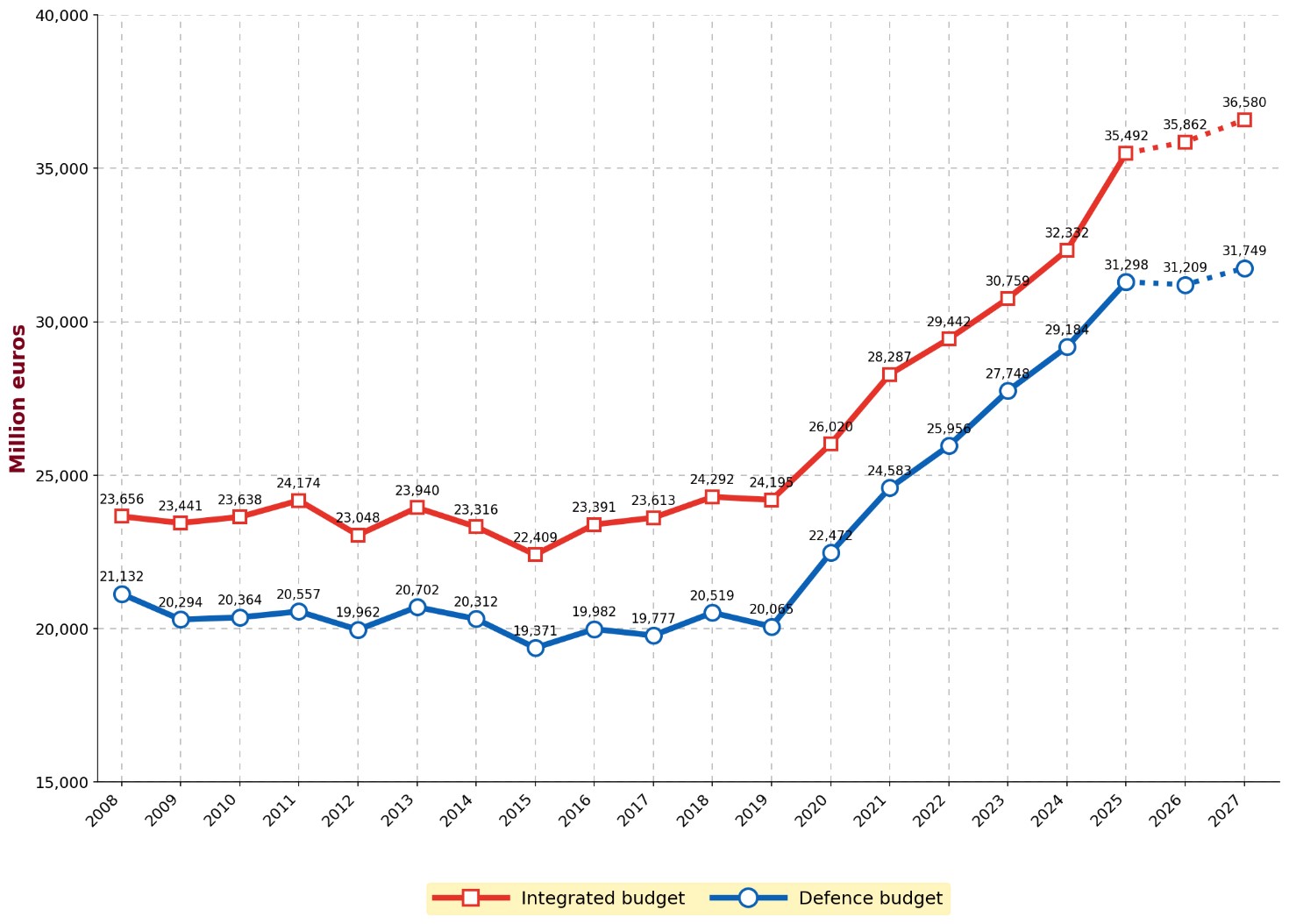

Within NATO, Italy reaffirmed its commitment to collective defence and burden-sharing. In 2025, Rome endorsed ambitious spending targets (up to 3.5/5 per cent of the GDP by 2035), framing increased defence expenditure as both a response to allied expectations and an investment in national security. Defence procurement choices and joint training initiatives were explicitly linked to the objective of enhancing interoperability with US forces, reinforcing Italy’s strategic relevance within the Alliance.

Defence policy: Strategic awareness and capability development

Indeed, defence policy emerged in 2025 as a core component of Italy’s international posture. Strategic awareness also evolved qualitatively. The Ministry of Defence contributed to the debate through a non-paper on hybrid warfare,[3] emphasising cyber security, space, protection of critical infrastructure and societal resilience. These domains were increasingly recognised as integral to national defence rather than ancillary concerns.

Italy’s defence posture continued to be shaped by persistent structural challenges, including personnel shortages, ageing equipment and organisational rigidities. The government acknowledged these constraints and argued for sustained, predictable investment rather than short-term or emergency-driven measures.

Figure 2 | Italian defence budget (2008-2027)

Source: Italian Ministry of Defence, Documento programmatico pluriennale 2025-2027, September 2025, p. 94, https://www.difesa.it/assets/allegati/3756/documento_programmatico_pluriennale_2025-2027_pdfa.pdf.

Italy in the enlarged Mediterranean and beyond

The Middle East and the so-called ‘enlarged Mediterranean’ were a central arena of Italian foreign policy in 2025. Regional instability, intensified by the war in Gaza and broader geopolitical tensions, reinforced Italy’s conviction that developments in this area have direct and immediate implications for Europe.

Italy maintained open channels of communication with all key regional actors, including Israel, Arab partners and the Palestinian Authority. While condemning the humanitarian consequences of the conflict in Gaza, Rome aligned itself with US-led attempts to stabilise the situation, supporting ceasefire initiatives and post-conflict reconstruction frameworks. At the same time, Italy conditioned any recognition of Palestinian statehood on the definitive marginalisation of Hamas, adopting a security-oriented and incremental approach.

In the enlarged Mediterranean, Italy sought to assert a degree of strategic autonomy by positioning itself as a bridge between Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Relations with key actors such as Egypt, Jordan and, increasingly, the Arab Gulf countries were strengthened through intensified political dialogue and economic cooperation. Engagement with Gulf partners was driven by shared interests in regional stability, energy security and investment, as well as by Italy’s ambition to diversify its diplomatic and economic partnerships beyond traditional Euro-Atlantic frameworks.

The Mattei Plan continues to represent the compass for Italy’s approach to Africa and the southern neighbourhood. Conceived as an integrated framework linking development cooperation, energy security, business projection and migration management, the Plan supposedly aims to promote mutually beneficial partnerships while reinforcing Italy’s leadership role in the enlarged Mediterranean. In 2025, Rome tried to expand the scope of the Plan, both geographically (by including new target countries) and thematically (for example, as far as debt relief Initiatives are concerned), although its actual Implementation and effectiveness still remain to be tested.

With regard to the Indo-Pacific region, instead, Rome aligned with EU and NATO partners in recognising its strategic importance, while avoiding a confrontational posture towards China. This cautious approach reflected Italy’s preference for economic engagement and risk management over rigid alignment or escalation.

Long term priorities: Energy and environmental policies, and the multilateral arena

Energy security remained a key component of Italy’s external action in 2025, closely intertwined with its engagement in the enlarged Mediterranean and Africa. Building on diversification efforts initiated after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Italy consolidated its role as a Southern European energy hub, strengthening partnerships with suppliers in North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. While gas diversification continued to dominate short-term priorities, Italy also promoted renewable energy cooperation and infrastructure development, presenting energy partnerships as drivers of economic growth and regional stability. These efforts were closely linked to broader diplomatic initiatives, including the Mattei Plan, which positioned energy cooperation at the intersection of development, security and migration management.

At the European level, Italy adopted a rather critical stance towards the implementation of the Green Deal. With regard to EU climate objectives, the government argued for greater flexibility in timelines and instruments to supposedly safeguard industrial competitiveness and social cohesion. Rome advocated for the so-called ‘technological neutrality’, while the country’s decarbonisation efforts slowed significantly. Notably, for the first time during her tenure as Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni did not attend COP30 in Brazil.

More generally, as regards Rome’s place within the multilateral arena, 2025 may prove to be a turning point. As the Trump administration showed more and more disdain towards the Institutions and organisations of multilateralism that Washington itself had helped to build, Rome primarily used multilateral fora to reassert its national (and domestic) priorities. Still, for a middle power with limited capabilities such as Italy, advancing the latter inevitably requires a functioning multilateral system, therefore placing the country in a delicate position amidst an increasingly unstable world.

Leo Goretti is Head of the “Italian foreign policy” programme at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI). Filippo Simonelli is Junior Researcher in the “Italian foreign policy” programme at IAI.

This brief partly draws on the 2025 edition of IAI’s annual report on Italian foreign policy titled: “L’Italia nel mondo instabile”, coordinated and edited by Leo Goretti and Michele Valensise and developed with the support of the Fondazione CSF-Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo.

[1] See the official website: https://www.urc-international.com.

[2] See European Parliament, Parliament Greenlights First-Ever European Defence Industry Programme, 25 November 2025, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20251120IPR31493.

[3] Italian Ministry of Defence, Countering Hybrid Warfare: An Active Strategy. Non-paper, November 2025, https://www.difesa.it/assets/allegati/83732/non-paper_countering_hybrid_warfare.pdf.