Titolo completo

Moldova’s EU Accession Prospects after the Elections: A ‘New’ Power Dynamic and the Return of Euroscepticism

|

The Moldovan elections on 28 September led to an outcome that enables the country’s European Union integration to proceed smoothly, without any risk of obstruction. Despite widespread fears that the pro-EU forces might lose the elections, the ruling Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) secured 55 out of 101 seats. The four opposition groups – the Patriotic Bloc, the Alternative Bloc, Our Party and Democracy at Home – each with varying degrees of Euroscepticism – won 46 seats and will also be represented in the newly elected parliament. These elections were framed as a choice between EU integration and the threat of a Russian invasion, similar to that in Ukraine, which aimed to “turn Moldova against Europe”.[1] As such, this “geopolitical” battle[2] was closely followed in the West, which has characterised the victory of the ruling pro-EU party as a setback for Russian influence in the region.[3]

Threats of potential disorder following the election result have proved to be misplaced. Prior to the election, Moldova’s intelligence service warned of violent protests allegedly backed by Russia, citing reports of protestors being trained on Serbian territory by Russian intelligence forces.[4] Despite these reports and opposition parties criticising the fairness of the elections, the majority have refrained from engaging in any unlawful post-electoral actions. Only the Socialists from the Patriotic Bloc – the largest opposition group with 26 seats – called for street protests and international diplomatic intervention, citing allegations of serious electoral irregularities.[5] Indeed, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Election Observation Mission assessed the elections as “competitive”, while also recognising a range of Russia-linked external interference, including cyberattacks, disinformation, electoral corruption.[6] At the same time, the mission reported various shortcomings within Moldova’s electoral system relating to: i) the impartiality of the Central Electoral Commission; ii) the polarised media environment; iii) limited effective remedies for electoral candidates; iv) the relocation of certain voting stations for residents from the breakaway Transnistrian region.[7]

As in the previous parliament, the PAS majority faces serious challenges: economic stagnation, a stalled dialogue with the Russia-leaning Gagauz autonomy and a crisis-prone Transnistrian region, where gas supply shortages are likely to recur this winter.[8] To move Moldova closer to its 2028 EU accession target, future PAS-led government(s) must deliver tangible socio-economic improvements to maintain the EU’s often fragile legitimacy among the Moldovan population. While doing so, the PAS-Sandu political alliance will also need to navigate and mitigate obstacles from within EU member states that could arise from the ‘one package’ enlargement that also includes Ukraine.

Building on earlier pro-EU political wins

Heavily influenced by the East-West geopolitical dilemma, the ruling PAS party amassed 792,557 votes, accounting for 50.2 per cent of the total votes. To a large extent, the positive outcome for PAS stemmed from the 2024 electoral success of the party’s informal leader, Maia Sandu, who was re-elected as president with 55.3 per cent of the votes (930,238 votes). PAS’s results also resemble the outcome of the 2024 constitutional referendum, in which 50.3 per cent (749,719 votes) supported incorporating EU accession into the country’s Constitution (Article 141[1]).

Although it is believed that vast majority of pro-EU voters cast their votes for PAS, other electoral candidates also appealed to supporters of EU integration. Four electoral candidates from the Alternative Bloc, Our Party and Democracy at Home were able to accumulated votes from dissatisfied pro-EU voters who has become increasingly Eurosceptic due to the socioeconomic crisis. Overall, however, their anti-integration platform combined with plans for sectoral cooperation with Russia in the energy and trade – rather than embracing Russia as a strategic partner – failed to gain broad support. Of more significance for result was the opposition’s plans to normalise ties with Russia to secure cheaper natural gas and legislative proposals targeting ‘foreign agents’,[9] taking inspiration from the Georgian case – which triggered widespread mistrust amongst the electorate.

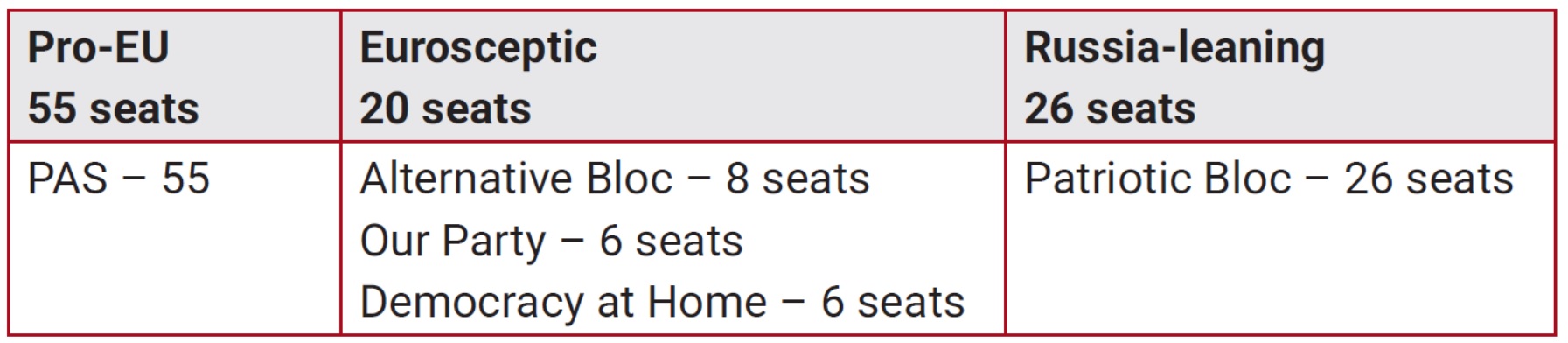

Indeed, the PAS-led government was able to weaponise anti-Russian sentiment during the campaign effectively, including by using war-related imagery of Russian airstrikes in Ukraine. While the genuinely pro-Russian stance of the Patriotic Bloc – whose leaders visited Moscow in the months leading up to the elections and held meetings with Russian officials[10] – provided fertile ground for these efforts, the ruling PAS also actively fostered public suspicion that the Alternative Bloc, Our Party and Democracy at Home could quickly become pro-Russian proxies. These suspicions prompted Romanian authorities to impose a travel ban on Ion Ceban, the mayor of the capital city, Chișinău, and one of the leaders of the Alternative Bloc. Despite Ceban’s frequent visits to Romania during his time as mayor between November 2019 and July 2025,[11] the Romanian authorities justified their decision to ban Ceban’s entry into the country and the wider Schengen area by citing threats to national security.[12] This restriction may have weakened the Alternative Bloc’s ability to attract pro-EU voters who had lost trust in PAS. Nevertheless, the public discourse and electoral programmes of the parties entering Parliament suggest a more nuanced political landscape than a simple pro-EU versus pro-Russian dichotomy. While the PAS remains the only explicitly pro-EU party, the new Parliament will have a strongly Eurosceptic core made up of the Alternative Bloc, Our Party and Democracy at Home (see Table 1).

Table 1 | The distribution of seats based on the election outcomes

Source: Author’s inferences drawn from the electoral programmes of political parties and public discourse.

Whether PAS remains the only pro-EU political force in parliament will become clear as the law-making process unfolds. Aside from the openly Moscow-leaning Patriotic Bloc, the other three opposition groups have the ability to use their parliamentary positions to either challenge or advance PAS’s European aspirations should they wish to do so.

The ‘new’ parliamentary dynamics

As in the previous parliament, the PAS has secured top-down political control over state institutions and will not require support from other intra-parliamentary political forces to pursue its political agenda within the executive branches of power. As a result, President Sandu is well-positioned to strengthen Moldova’s external relations. Securing a comfortable majority for PAS was crucial to maintain Sandu’s relevance both domestically and in relations with Western partners. During the last legislative cycle, the alignment of PAS and Sandu contributed to a high level of political stability. However, this consolidation of power also limited scope for broader parliamentary engagement. As PAS held a dominant position, transparency and inclusiveness in the legislative process declined. Civil society actors have repeatedly criticised PAS for the frequent changes to the parliament’s working agenda. The most notable case occurred on the 10th July during the final plenary session of the outgoing parliament, when PAS passed 79 draft bills and decisions in under 7 hours.[13] Such parliamentary majorities – often referred to as ‘voting machineries’ – are less likely under the new parliamentary composition which now includes more diverse and revitalised opposition forces.

The new parliament features opposition groups composed of both established and new political forces. The Patriotic Bloc, which includes the Socialists and Communists, remains the only returning alliance. The other three opposition groups – Our Party, Democracy at Home and the Alternative Bloc – are relative newcomers. Our Party and Democracy at Home, each with six seats, have previously engaged in populist tactics, often involving the release of controversial or scandalous information. Their past conduct suggests they are likely to adopt a confrontational stance, acting as vocal blockers rather than cooperative partners. In contrast, the Alternative Bloc, led by Ceban (who retains his post as mayor of Chișinău),[14] is more complex. The bloc’s other leaders – Alexandr Stoianoglo, Ion Chicu and Mark Tkachuk – are expected to follow divergent political agendas, making internal unity difficult. If the Alternative Bloc remains cohesive, it could leverage its parliamentary numbers to negotiate with PAS and strengthen Ceban’s influence in governing the capital. The opposition’s diversity – with four different political forces – could however lead to significant disunity, ultimately benefitting PAS. Thus, the dynamics in the new parliament are gravitating around two main poles of power: one led by PAS and another centred on the Patriotic Bloc (see Table 2). Smaller parliamentary groups – Alternative Bloc, Our Party and Democracy at Home – are likely to form situational alliances with both the pro-EU PAS and the Russia-leaning Patriotic Bloc, provided it maintains its internal cohesion.

Table 2 | Probable ‘permanent’ and ‘situational’ alliances in the incoming parliament

Source: Author’s estimates based on the potential permanent[15] and situational alliances.

The external ‘pivoting’

The new composition of the Moldovan parliament somewhat reduces the influence of external policy preferences within it. There is no doubt that EU institutions will continue to rely on PAS in their engagement with Moldova, leveraging the party’s close political ties with the European People’s Party. The strong alignment of President Sandu, the future government and the PAS parliamentary majority makes it highly likely the EU will expect a disciplined, unconditional implementation of commitments made by Chișinău’s political leadership.

At the same time, the Patriotic Bloc will seek to promote a dialogue with Russia, albeit in a vague terms to shield itself from accusations of committing “state treason”.[16] In July 2024, the PAS majority amended the Criminal Code, broadening the definition of guilt to include the provision of ‘aid’ to a foreign state engaged in hostile activities that threaten Moldova’s national security.[17] This legislative change aligns with the 2023 national security strategy – approved by the PAS majority – which designates Russia as an “existential threat” to the country.[18] Under stricter rules governing political engagement with Russia, the leaders of the Patriotic Bloc have framed their call for normalising relations with Moscow primarily in economic terms, highlighting the benefits of resuming natural gas imports at a lower price.

The newcomers – Alternative Bloc, Our Party and Democracy at Home – will introduce different perspectives into the Moldova’s traditionally rigid political discourse centred on the East-West divide. These parties will need to seek to move beyond the established EU-centric framework, which primarily serves to legitimise the PAS-Sandu axis. The Democracy at Home party has a clearer profile due to its explicit support for a ‘sovereignist’ agenda that rejects the delegation of core state functions to the EU. As part of this, the party plans to deepen its 2024 cooperation agreement with the Romanian far-right Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR), which leads the Romanian polls for September with 41 per cent of public support.[19] Party leader, Vasile Costiuc, has stated that the Democracy at Home party will prioritise the Bucharest-Washington axis in its foreign policy orientation. The party also aligns itself with the ‘Make Europe Great Again’ movement,[20] which brought together members of the European Conservatives and Reformists in Chişinău shortly before the elections.

Despite previous meetings in Washington, Ceban’s Schengen area travel ban constrains the National Alternative Movement – part of the Alternative Bloc – in building external alliances. Similarly, Our Party faces uncertain prospects regarding its foreign orientation because it did not signal any specific preference through socialisation with foreign political elites. These are the only two opposition forces in parliament grappling with an identity crisis. Given their ambiguous or non-existent affiliations with Western political actors, both parties are likely to struggle to counter accusations of acting as covert Russia proxies. In an attempt to establish a clearer political profile in the Moldovan parliament, they may seek alignment with sovereigntist circles in Washington and/or Brussels.

Table 3 | The differentiation based on external pivoting

Source: Author’s inferences based on the electoral programmes of the political parties and the public discourse.

Three ‘weak spots’ in Moldova’s EU accession: Turning electoral goals into realpolitik

A key priority for PAS in the newly elected parliament will be aligning the national legal framework with the EU acquis. The PAS government aims to accelerate the ‘Europeanisation’ of Moldovan legislation as part of the broader accession process. However, unlike in the previous legislative, the new parliamentary opposition – Alternative Bloc, Our Party and Democracy at Home – is likely invoke the protection of sovereignty to hinder the swift adoption of laws, a process PAS has relied on over the past four years to advance its aim of EU accession. Three points of contention are likely to significantly influence the parliament’s dynamic around European integration: the 2028 target date for EU accession, the ‘coupling’ with Ukraine and continuing Russian influence.

The 2028 deadline for EU accession set by PAS seems overly optimistic. To date, the EU has only publicly stated that Montenegro could join by 2028 and Albania by 2029,[21] without providing any timeline for Moldova. Failing to meet this self-imposed deadline could heighten scepticism in the feasibility of EU integration among Eurosceptic groups represented by the parliamentary opposition. Furthermore, the PAS government must decide whether to keep supporting the ‘one package’ approach to enlargement, which currently ties Moldova’s accession prospects to those of Ukraine.[22] This ‘coupling’ strategy carries growing risks: with far-right forces in Slovakia and the Czech Republic potentially joining Hungary in vetoing Ukraine’s accession, Moldova could find itself mired in uncertainty.[23] Lastly, failing to meet the 2028 deadline and stalled negotiations due to the ‘coupling’ with Ukraine, would provide fertile ground for extensive anti-EU disinformation campaigns orchestrated by Russia.

In conclusion, Moldova’s recent elections were marked by a heavily geopoliticised context, resulting in a parliament still dominated by the pro-EU PAS. However, the road ahead appears increasingly difficult, as the new parliament is slightly more Eurosceptic than its predecessor. To progress towards EU accession, the Moldovan government may need to lower public expectations about the 2028 deadline for EU membership, in light of growing Eurosceptic sentiment in society and the continued appeal of anti-EU Russian narratives. For the accession process to be sustainable and credible, quality must take precedence over speed – something that can be overlooked when EU ambitions are too closely linked to electoral cycles. However, in a geopolitical setting where Russian influence persists, Moldova could be forced to adopt a more pragmatic, realpolitik approach by establishing a framework that more carefully balances national interests with the commitment to external strategic goals, to keep its European integration hopes resilient until the EU accession comes to fruition.

Denis Cenusa is associated expert at the Geopolitics and Security Studies Center (Lithuania) and at the Expert-Grup (Moldova), non-resident fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis (United States), and PhD candidate at Justus-Liebig-Universität (Germany).

[1] European Parliament, President Maia Sandu Says Russia Wants to Turn Moldova against Europe, 9 September 2025, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/es/press-room/20250905IPR30176.

[2] Stasiuk, Yurii, “EU and Russia on the Ballot in Moldova’s Existential Election”, in PoliticoEU, 24 September 2025, https://www.politico.eu/?p=7216665.

[3] Verseck, Keno, “Moldova’s Resounding ‘Yes’ to Europe — and ‘No’ to Russia”, in Deutsche Welle, 29 September 2025, https://www.dw.com/en/a-74178384.

[4] “Moldova Detains 74 People over an Alleged Russia-backed Unrest Plot around Key Election”, in AP News, 22 September 2025, https://apnews.com/article/293ee902e878ce1efcca339759eb06d0.

[5] Gridina, Marina, “The PSRM Rejects Parliamentary Election Results, Threatens Protests”, in MoldovaLive, 7 October 2025, https://moldovalive.md/?p=37568.

[6] OSCE et al., Moldova, Parliamentary Elections, 28 September 2025: Statement of Preliminary Findings and Conclusions, 29 September 2025, p. 1, https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/moldova/597800.

[7] Ibid., p. 1 and 3.

[8] “Moldovagaz Head Said Transnistria Is Provided with Gas until October 16, and Negotiations Are Underway on Further Supplies”, in Infotag, 9 October 2025, https://www.infotag.md/economics-en/327291/.

[9] Rotari, Iurie, “The Government Criticises a ‘Foreign Agents’ Law Proposed by the pro-Russian Opposition” (in Romanian), in Radio Free Europe/Moldova, 3 April 2025, https://moldova.europalibera.org/a/33371272.html.

[10] Leahu, Alexandrina, “Dodon, Vlah and Tarlev Visit Moscow – Russian Deputy Prime Minister Pledges Engagement If Moldova’s Government Changes”, in MoldovaLive, 11 July 2025, https://moldovalive.md/?p=35409.

[11] Gridina, Marina, “Ion Ceban Met with Marcel Ciolacu: Together with Colleagues from Romania, We Have to Implement Many Beautiful Projects”, in MoldovaLive, 1 April 2024, https://moldovalive.md/?p=21797.

[12] “Nicușor Dan, about the Ban Imposed on Ion Ceban: It Is a Matter of National Security”, in Cotidianul, 14 July 2025, https://cotidianul.md/en/8774.

[13] “The Rush at the Last Parliament Session. Promo-LEX Condemns the Lack of Transparency in the Examination and Approval of Projects”, in Cotidianul, 12 July 2025, https://cotidianul.md/en/8657; Promo-LEX, Summary of the Last Plenary Session of the Parliament (July 10, 2025) of the Spring Session. Promo-LEX Conclusions at the End of the Parliament’s Mandate (in Romanian), 12 July 2025, https://promolex.md/?p=37769.

[14] Tobultoc, Mihaela, “Ion Ceban Elects City Hall, Not Parliament: ‘I Will Remain Mayor, As I Promised’”, in Cotidianul, 9 October 2025, https://cotidianul.md/en/15766.

[15] Two candidates on the PAS electoral list represented a smaller pro-EU opposition force, Platforma DA: Dinu Plîngău and Stela Macari. Once joining the parliament, they announced that they would separate from PAS, continuing to cooperate on the EU integration agenda.

[16] Benea, Radu, “New Definition of ‘Treason’, Approved by Parliament in Final Reading” (in Romanian), in Radio Free Europe/Moldova, 6 June 2024, https://moldova.europalibera.org/a/32981983.html.

[17] See Article 337 in Moldovan Parliament, Criminal Code of the Republic of Moldova, June 2024, https://legislationline.org/sites/default/files/2025-03/MDA-64897.pdf.

[18] See Point 13(1) in Moldovan Presidency, National Security Strategy of the Republic of Moldova, 15 December 2023, https://presedinte.md/eng/strategia-securitatii-nationale.

[19] Coșlea, Alexandra, “Avangarde Poll. AUR, Rated Almost as Much as PSD, PNL and USR Combined” (in Romanian), in HotNews, 20 September 2025, https://hotnews.ro/?p=2069735.

[20] Ziarul de Gardă, “The MEGA AUR Conference that United Simion, Furtună, Filat, Costiuc and Munteanu” (video in Romanian), in YouTube, 2 August 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HJkA6XNZNw8.

[21] European Western Balkans, Kos: Montenegro Could Join the EU 2028, Albania in 2029, 2 September 2025, https://europeanwesternbalkans.com/2025/09/02/kos-montenegro-could-join-the-eu-2028-albania-in-2029.

[22] Jozwiak, Rikard, “EU Decoupling Debate: Moldova and Ukraine’s Path to Membership under Scrutiny”, in Radio Free Europe, 8 September 2025, https://www.rferl.org/a/33524085.html.

[23] Jorge Liboreiro, “EU Resists ‘Difficult’ Decoupling of Ukraine and Moldova’s Accession Bids”, in Euronews, 2 September 2025, https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2025/09/02/eu-resists-difficult-decoupling-ukraines-and-moldovas-accession-bids.